Any true bibliophile knows that stalking the shelves of a bookstore with a fellow-shopper who is both educated in the ways of books and informed in your own particular tastes is much more fun and productive than browsing alone. It helps to have that extra pair of eyes skimming the spines and to have another intelligent opinion with which to discuss potential finds. I’m quite fortunate to have both of those qualities in one person: my twin brother.

Recently he and I were browsing at Gabriel Books in Northampton, MA and he came across this little item. Most book-collectors would pass over it because the title is not particularly collectible and the cover is a bit beaten up, but my brother knew of my interest in marginalia and thought I’d enjoy adding this to my collection.

Many collectors can be quite close-minded about marginalia, feeling that unless the markings have associative value related to the book (for example, the signature of the author, or proof markings by a reviser preparing a subsequent edition, or notes written by a notable or famous owner) reader's markings actually devalue a volume. I'm not terribly impressed by these kinds of collectors: their interests are purely pecuniary, thus they lack both the inductive imagination and the intuitive curiosity that are the hallmarks of a true bibliophile. In some ways I'm glad for that, though; it means more of these great finds for those collectors who can best appreciate the stories they have to tell.

The book is a first edition of the textbook A Latin Grammar for Beginners, written William Henry Waddell, Professor of Ancient Languages at the University of Georgia, Athens. The book was published in February, 1871 by Harper & Brothers of Franklin Square, New York and is listed in the Editor’s Literary Record & Review of the November 1871 issue of Harper’s Magazine. Harper published a subsequent edition in 1873 which is much more common; the 1871 edition is rare and valued at approximately $20-$30.

The pages measure 11cm x 18.5cm; the book was printed in duodecimo, in eight gatherings signed [A1], A2-D2. Each initial gathering (A1, B1, C1, D1) has four leaves, each ultimate gathering (A2, B2, C2, D2) has eight leaves. The initial leaf of A1 is a blank flyleaf; two additional blank leaves (not part of D2) end the volume. The pagination runs [1-9], 10-86; the final five leaves are publisher’s advertisements, paginated [1]-2, [1]-[4], [1]-[4]. The binding is a soft red leather on light cardboard boards, with gold impressed title on the front, impressed double-line border on front and back, and impressed publisher’s monogram on the back; the page edges are inked red all around. The binding is worn slightly and the corners (particularly the lower, outer corner on the front) a bit beaten up. Inside the front cover my copy has a yellow bookstore sticker for “Leary, Booksellers” of 5th & Walnut, Philadelphia, a landmark of Philadelphia’s book trade from 1849 through its closure in 1968 (when it closed it was the largest used bookstore in the U.S.; its stock was so large that in the process of clearing it out for closure an original Dunlap printing of the Declaration of Independence was found and sold for $400,000).

A preface by Waddell presents the book as a companion to his previous Greek Grammar for Beginners (published by Harper in 1869) and explains that its target audience is the high school or “the lower classes in our American colleges”. Perhaps most intimidating is his suggestion that the book “be committed to memory, from cover to cover, the first time the pupil goes over it”.

As might be expected, the contents of the book are organized along an old-fashioned linear pedagogical course of Latin language education, starting with a section on orthography, moving through an extensive series on etymology (noun declensions, verbal conjugations, etc.), and ending with two brief sections on syntax and prosody (which uses Horace for a case study).

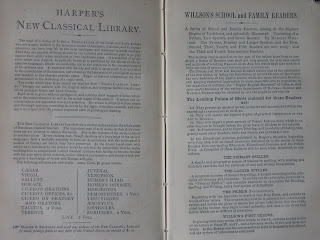

The advertisements at the end of the book (which run 10 pages--the same amount of space as is dedicated to the prosody section and five times as much as space as is dedicated to the orthography section) are for other classical textbooks published by Harper. These include Waddell’s Greek Grammar, Harper’s Greek and Latin Texts series of classical text editions, Harper’s New Classical Library series, Willson’s School and Family Readers, and Loomis’s Mathematical Series. As with most publisher’s advertisements from this period, these list basic physical features of the books (size, price, pagination), copious endorsement quotations from reviewers and scholars, features that make them educationally useful, and in the case of Harper’s Greek and Latin Texts a listing of professors who currently use the books,

The Waddell family was a fixture at the University of Georgia in the turbulent years leading up to, during, and after the Civil War. William Henry (shown below) was the son of Moses Waddell, who had served as the fifth president of the University from 1819 through 1839. He was probably also related to James P. Waddell, tutor at the University from 1822 to 1824 and full Professor of Ancient Language from 1836 to 1856. Another James Waddell (different man) also completed his undergraduate studies at the University around this time and went on to become a lawyer and member of the Georgia state legislature. A John Waddell, also a lawyer apparently, was issued an honorary degree by the University in 1864.

William Henry had been a student at the University from 1848-1852 and a member of the campus branch of Phi Beta Kappa. His wife was Mary Bumby Sue Waddell. According to the University’s Catalogue of the trustees, officers, and alumni, Waddell began teaching as a tutor at the University in 1853, moved up to adjunct in 1858 and was promoted to lecturer two years later; he was elected full professor in 1872, and resigned in 1878. During his tenure as professor, he was one of 11 faculty members at the University (including the Chancellor, Patrick Hughes Mell).

Waddell was thus a lecturer during the years of the Civil War, at a time when the University granted permission to the Confederate government of the state to use part of the campus as an “ophthalmic” hospital. On June 19, 1864, Waddell expressed concern that the college would be unable to reopen that September because “the Dormitories [are] full of blind soldiers and Refugees.” According to a survey completed for the University’s Centennial Alumni Catalogue in 1901, Waddell died in 1880. His family name lives on as a street name near the campus and in the (misspelled) Waddel Hall, home of the University’s Rusk Center for International Law.

The advertisement in Waddell’s Latin Grammar promoting Harper’s Greek and Latin Texts notes that, “The volumes are handsomely printed in a good plain type, and on a firm fine paper, capable of receiving writing ink for notes...” These books were meant for practical purposes, meaning that many old textbooks often have interesting marginalia recording how their student-owners used them (or neglected to use them). This copy is no exception, though the markings suggest the original owner was less interested in the Latin lessons assigned to her and more interested in the schoolteacher assigning them.

The copious writing in the book appears to be from two or three owners, in multiple media (black ink, pencil, blue pencil, purple ink), but one late nineteenth-century hand dominates: Miss Jennie Venable.

Jennie covered her book in many ramblings, very few of which are related to the content of the textbook, many of which are in verse, most of which center around her romantic fascination with “Mr. Willie Davis”, a man who, from the context, seems to have been her high school Latin teacher. The first several pages of the book are covered with flirtatious notes and poems about how handsome Mr. Davis is and how she hopes he will not forget her (some of the writing is in pencil and has been, perhaps in the interests of delicacy, erased). “Mr. Willie Davis is very handsome”, “Willie Davis is so handsome and dashing”, is a constant refrain.

When Jennie does attend to her Latin it is to scribble the word “amo” (I love) in various permutations and conjugations. Markings directly related to the content of the book (usually ticks and crosses by various lessons) vanish after page 39 (the second conjugation, subjunctive mood), suggesting either Jennie gave up on the Latin language for the second half of the school year or else the course did not proceed beyond that point (on the inside back cover an erased pencil note reads “< > wish I could go home home home”). She does write some other remarks unrelated to the course or Mr. Davis (“Let virtue be your guiding star”, for example).

Two verses on the verso of the front flyleaf are in different hands and are both addressed to, rather than written by, Jennie:

May happiness around thee shine

While germs of joy thy brow entwine

May lifes bright river gently flow

And all thy fortune brightly glow.

Laura

Forget me not I only ask

This simple boon of thee

And may it be an easy task

Sometimes to think of me

To Jennie

from Florence

An unsigned penciled verse on the verso of the title page is possibly in Jennie’s hand:

You I love and will forever,

You may change but I will never.

If separation be our lot,

Dearest one forget me not.

On the recto of the final flyleaf, another friend has inscribed a touching verse to Jennie:

Remember me when far away

Remember me when awake

Remember me on thy wedding day

And send to me a piece of cake.

The best wishes of a friend

Hattie Strickey

To Jennie Venable Miss.

A version of this poem--though slightly different--appears to have been written on the bottom of the flyleaf verso (beneath Florence’s poem) but subsequently erased. The name of Strickey appears elsewhere in the pages of the book as well.

A change in Jennie’s affections for Mr. Davis seems to have struck sometime over the course of the school year, by the time the class reached page 25 in the textbook (in the middle of the lesson on comparative adjectives). On this page she expresses her interest in “Cousin Newton Harrold”, who is “the sweetest sweetheart so he is”. On p. 27 this budding crush is reiterated more confidently: “I love cousin Newton so I do.”

On the recto of the penultimate leaf, Jennie provides a lengthy meditation on her incestuous plight:

Well I do love cousin Newton ofcourse [sic] it is to be expected

I would love my dear cousin my darling little Newton

my little genius, how could I help it. I do not

Harm any one for loving him except it does make

me jealous for any one to love cousin ofcourse I

love him only as a dear fond cousin + nothing

else on earth, but he is powerful sweet, yes he

grins so prettily + shows his beautiful pearly

white teehh teeth, I wish cousin Newt- loved

me. If he loved me like I loved him

his knife can cut our love in two.

Perpendicular to this, in pencil along the bottom margin of the page, is the somewhat histrionic exclamation:

Oh! Dear me what will be my f< > [fate?]

But, alas, the heart of a young lady is ever fickle: yet another crush is expounded upon on the verso of this leaf as two different hands engage in dialogic note-writing back and forth.

Wallis D is much handsomer

than G------ I think.

Well he was called a

fool I don’t think in

my soul that he is

as big a fool as some

body else in Bridville.

The name of this bigger fool was apparently written below the comment but has been judiciously scratched out. (I haven’t been able to find a “Bridville”, but it may be a misspelling of “Bridgeville”, which is the name of a town in Delaware and a town in Pennsylvania, which may explain how the book ended up at Leary’s in Philadelphia.) This writing is then followed by an illegible, erased comment about Mr. Davis. Below that is another cryptic inscription, once again in Jennie’s hand and written in pencil:

I think Mr. Willie Davis is

handsome, but I think somebody

else a great deal handsomer.

As I finish transcribing these melodramatic lines, I can only wonder what Professor William Henry Waddell would think of his textbook being used as an outlet for such adolescent outbursts. And my eye is drawn to what is perhaps the most coincidental of the scribblings in this book pulled from the shelf for me by my twin brother. Written in Jennie’s ornate, purple-ink hand on the recto of the front flyleaf, is a random jotting that seems clearly to read: “Your Twin find.”

No comments:

Post a Comment