On Friday I overheard some undergraduate students discussing the 2016 Olympics contention. One pointed out that Tokyo should be eliminated from the competition because “Beijing held an Olympics already, so Japan has had its chance.”

In that student’s honor, this week’s book is the second American edition of the Reverend Isaac Taylor’s Scenes in Asia: for the amusement and instruction of little tarry-at-home travellers. As the title implies, the book was meant for young students to read in order to gain an understanding (though a misleading one, on which more below, but see the photograph to the left for an example) of foreign cultures without leaving the comfort of their home.

My copy was published in 1830 by the celebrated Hartford, Connecticut publisher of Americana, history, biography, and law, Silas Andrus; it was printed in stereotype by John Conner of New York City. Taylor’s popular book, which was part of the series Books for Young People, was first published in 1819 by John Harris and Son of London; subsequent editions followed quickly from Harris in 1821, 1822, 1826, 1827, and 1829. Andrus’s first American edition appeared in 1826. Later American editions were published by Erastus Pease of Albany in 1843 and 1850. Despite this extensive print run, extant copies of these early editions are valued quite high on the market; interestingly, I can find no copies of the 1830 Andrus currently for sale.

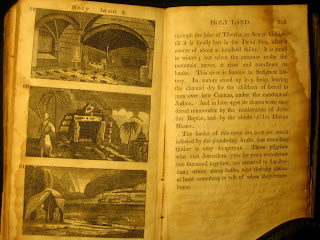

The book is bound in pressed, bluish boards with a leather spine; gilt lettering and lines once decorated the spine, but my copy is so cracked and split that they are difficult now to discern. The paper is a soft, fairly cheap linen stock with mesh-lines but no watermarks; each page measures more or less 9cm x 14.5cm. Conner’s printing was workmanlike, but there is some evidence of complications during the stereotyping process. The book was printed in octavo; I’ll skip the collational formula, which is generally sound, though in some places short gatherings hint at problems with certain sheets. The pagination runs [i]-vi [1]-124. Within each chapter there are numbered sections about aspects of that nation or region's culture; the numbers refer to illustrations found on some of the facing pages. Because the book was printed by stereotype, the illustrative plates are conveniently integral to the gatherings in which they appear and did not have to be tipped in or inserted after printing. As noted, the condition is rather rough: the boards are scuffed and corners deeply bumped, pages are somewhat loose from the cracked binding and often water-stained, the leather spine is severely chipped, and some leaves are torn (some moderately and some, particularly engravings and the initial map, almost entirely gone).

There are no marginalia or reader’s marks in the copy, but the recto of the flyleaf does have a gift inscription written in watery copper ink and a nineteenth-century hand:

William W Burnham

Presented to his cousin

Hubert North

I’ve been unable to located Burnham with any confidence, though in the 1868 Manual of the corporation of the city of New York there is a “William W. Burnham” listed as clerk to the Collector of City Revenues. Working from the fact that Andrus was located in Hartford (though my copy may have retailed and subsequently traveled anywhere), I tried to find a contemporary Connecticuter with the name of Hubert North. The only man of this name I can find lived in New Britain, Connecticut in the 1870s and was the “Son” in the wire, ring, clasp, and hook-manufacturing firm “Alvin North & Son”, located at the corner of East Main and Stanley Streets since 1812. I have no idea if this is the man who owned my copy, but it is not impossible. For reasons I cannot fathom (accident? page-marker?) an old, bent steel nail has been pressed into the gutter of the final opening, between the last page of content and the rear pastedown.

The book begins with a fold-out map of Asia (unfortunately mostly torn out in my copy), on which a line traces the route the book takes through various countries. A doggerel verse at the start introduces the reader to the book’s objective. The narrator then moves from region to region and country to country, covering a region encompassing the Middle East, Turkey, China, Japan, India, and Indonesia, giving a subjective, often grossly inaccurate account of local customs, peoples, and sites, as well as citing stories from ancient history. All is written in a simple, sometimes amusing style. Interspersed throughout the book are illustrative plates (drawn from imagination, not from life), engraved by Taylor himself and occasionally short summative poems that put the chapters’ main points into memorizable verse.

The book ends with a concluding verse mocking and decrying the “pagan” religions of the people of Asia and thanking God for Britain, Jesus, and the Bible. Taylor was, after all, a reverend as well as a writer and engraver, so it should come as no surprise that the bulk of his book is concerned with (ill-)reporting Asian religions and rituals and making local traditions sound as gruesome, barbaric, and crude as he possibly can. (Google Books has scanned the full text of the 1826 fourth edition; the contents are largely the same as that in my 1830 copy and giving them a quick scan will give you a good idea of what I mean.)

The life of Isaac Taylor has been adequately detailed by his descendant, Robin Taylor Gilbert, in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography:

Isaac Taylor (1759–1829), engraver and educationist, was born in London on 30 January 1759, the second son of Isaac Taylor (1730–1807), engraver, and his wife, Sarah Hackshaw, née Jefferys (1733–1809). He spent his early years at Shenfield, Essex, and was first educated locally, probably at Sir Anthony Browne's School in Brentwood, before briefly attending a school in the City of London. Like his brother Charles Taylor (1756–1823) he was apprenticed to his father as an engraver and may later have become a pupil of Francesco Bartolozzi.

One of Taylor's first commissions was to oversee the preparation of the plates for Abraham Rees's revised edition of the Cyclopaedia of Ephraim Chambers. This work and Taylor's many discussions with Rees were, by his own account, what first filled him with a thirst for knowledge. In 1777 and in 1780 he exhibited landscapes and drawings at the Incorporated Society of Artists, of which his father was secretary. From an early age Taylor became a committed member of the Fetter Lane Independent congregation in London and was prevented from seeking ordination as a young man only by severe illness. Throughout his life he rose early and spent the first hour of every day, and usually the last also, in prayer.

On 18 April 1781 Taylor married Ann Martin (1757–1830); three sons and three daughters of the marriage survived to adulthood. The couple first set up house in Islington. Taylor's capital was £30, supplemented by Ann's dowry from her grandfather of £100 and his own income of half a guinea a week for three days' work for his brother Charles, together with whatever he could earn for himself in the other three days.

Taylor used Ann's dowry to commission Robert Smirke to produce four circular paintings representing morning, noon, evening, and night, which he then engraved and sold. Between 1783 and 1787 he was engaged with his brothers and with several painters, including Smirke, in an enterprise to produce illustrations to Shakespeare's plays, The Picturesque Beauties of Shakespeare (1783–7). The success of this enterprise prefigured the later, larger project of John Boydell, in which Taylor was a leading participant (he received 500 guineas for an engraving of Henry VIII's First Sight of Anne Boleyn, 1802, after Thomas Stothard). It certainly drew Taylor to the attention of Boydell and won him the lucrative commission (250 guineas) to engrave The Assassination of Rizzio by John Opie; this work was awarded the gold palette of the Society of Arts for the best engraving of the year in 1790.

Taylor's success as an engraver lay in his great technical skill combined with a flair for design, qualities which he also demonstrated as a painter of portraits and landscapes. One of his finest achievements was Specimens of Gothic Ornament (1796), a series of engravings illustrating architectural details of the parish church of St Peter and St Paul in Lavenham, Suffolk. Later in his career he engraved the illustrations for Josiah Boydell's Illustrations of Holy Writ (1813–15), the designs for which were accounted the finest artistic work of his son Isaac Taylor (1787–1865). Thereafter his published engraving was confined to illustrations of books by members of the family.

In 1783 the Taylors moved to Holborn but the annual rent of £20 was high and the environment injurious to the health of a growing family, almost all of whom were prone to illness. In 1786 Taylor made the decision to move to the country and, after characteristically diligent enquiry about prices and amenities, rented for £6 per annum a large house, Cooke's House, in Shilling Street, Lavenham, Suffolk. There his two eldest children, Ann and Jane, and his business, flourished.

Taylor's sketchbooks from his time in Lavenham contain many fine drawings and watercolour portraits of family members and of local acquaintances. The garden at Lavenham also provided the setting for his best-known portrait in oils (1792; NPG), that of his daughters Ann Gilbert (1782–1866) and Jane Taylor (1783–1824). In 1792, however, the Taylors' landlord gave them notice to quit and Taylor bought, for £250, the house next door, which was then in a ruinous condition. Its renovation (interrupted by Taylor's contracting typhoid, which nearly killed him) cost a further £250, but his careful and imaginative planning transformed house and garden from dereliction to delight.

Taylor had become a deacon of the Independent congregation in Lavenham and was closely involved in the founding of a Sunday school there. In 1794 he might have become minister, had the congregation not shrunk from the appointment of one of its own number. In late 1795 Taylor, who was gaining a reputation as a preacher, was invited to become minister of the Bucklersbury Lane Independent congregation in Colchester. In January 1796, having accepted the call, Taylor and his family moved to Colchester, where they rented a house in Angel Lane (now West Stockwell Street). On 21 April 1796 Isaac Taylor was ordained.

The move to Colchester coincided with a period of high inflation and the collapse of the art market in the wake of the war with France. Taylor suffered ‘a grievous reverse of fortune’ (Autobiography, ed. Gilbert, 1.100) and was reduced to engraving dog collars. Taylor wanted his daughters to be able to earn their own living; as soon as they were old enough all the children were employed to assist in the engraving business. The boys, Isaac (1787–1865), Martin (1788–1867), and Jefferys Taylor (1792–1853), were formally apprenticed, but his daughters, who were both to become published writers, were tolerated, rather than encouraged, in their literary vocation.

In Lavenham, Taylor's successive workrooms had doubled as schoolrooms for his own children and later for those of neighbours too, Taylor giving instruction from his engraving stool as he worked. This practice continued in Colchester, providing a welcome supplementary source of income. Taylor's object was ‘to give them a taste for every branch of knowledge that [could] well be made the subject of early instruction’ (Family Pen, 126) and he believed that ‘a principal object of education [is] to prevent the formation of a narrow and exclusive taste for particular pursuits, by exciting very early a lively interest in subjects of every kind’ (ibid., 113). His teaching methods were original and he made much use of carefully drawn visual aids, in the preparation of which his older children assisted. In late 1798 he began a series of monthly lectures for young people, delivered free of charge in the parlour of his own house; these proved extremely popular and the programme continued for several years.

Later in life Taylor wrote, and illustrated with engravings, a large number of very successful educational books, including the Scenes series (‘for the Amusement and Instruction of Little Tarry-at-Home Travellers’), and two volumes, The Mine (1829) and The Ship (1830), for the popular Little Library series published by John Harris. He also produced a number of books for the young, of a religious and improving nature, including The Child's Birthday (1811), possibly originally written for his youngest child, Jemima (1798–1886), Advice to the Teens (1818)—the first recorded use of the word to denote young people—and Bunyan Explained to a Child (2 vols., 1824–5). The preface to this last book is revealing of Taylor's approach to education and to religion, warning parents against expecting their children to read ‘all the many hours a wet Sabbath presents’, lest they ‘make that day hated, which ought to be loved’ (p. iv).

In June 1810 Taylor, exasperated by the apparently ineradicable antinomian tendencies of many in his congregation, announced his resignation from his pastorate in Colchester. A year later he accepted a call from the congregation at Ongar, where he remained for the rest of his life, rejuvenating and expanding the congregation, stimulating the intellectual life of the small town, and earning the respect even of the Anglican clergy. He instituted weekly lectures and prayer meetings, restarted the Sunday school, and played a leading part in a thriving book society—the while continuing to exercise his profession as an engraver and producing more than twenty books. He rented, first, Castle House and then New House Farm, just outside the town, and finally, in 1822, he bought a house at what is now 10 Castle Street.

Taylor, who had a stocky frame and an appearance usually of rude health, was described as ‘a genial portly figure … his cheek ruddy with apple tints’ (Autobiography, ed. Gilbert, 2.94). However, his life was punctuated by serious illnesses, including a three-year period in his late fifties, during which he almost succumbed to successive bouts of rheumatic fever. For almost a decade thereafter he maintained a pace of life that eventually proved too much for his constitution. On 12 December 1829, after a short illness, he died at his home. He was buried on the 19th in the Independent chapel's burial-ground; his grave now lies under the vestry floor of the United Reformed church, beside those of his wife and of his daughter Jane.

No comments:

Post a Comment