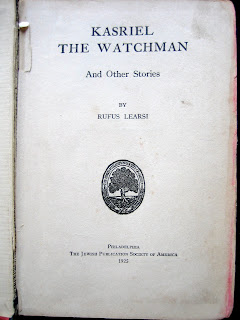

Yesterday marked the end of Hanukkah this year and so this week’s book was chosen as a small nod to my half-Jewish heritage. The title is Kasriel the Watchman and Other Stories, by Jewish American scholar, historian, short story writer, and playwright Rufus Learsi. It was published by the Jewish Publication Society of America in Philadelphia in 1925 and printed by H Wolff. There was evidently a reliable demand for the book as reprints of the first edition followed from the Society in 1929, 1936, and 1948. My copy is of the first.

Tracking down biographical information on Learsi has been frustratingly difficult. The nearest I can come to an understanding of the man is from looking at the evidence of his other publications; judging from when he published I would guess his life range was approximately 1890-1965. His earliest work was a biography of one of the nineteenth century founders of the Zionist movement, Theodor Herzl, published by the Judean Press of New York in 1916. In 1917 he published Brothers (Mizpah Publication Company, New York) and in 1919 Zionism: Its Theory, Origins, and Achievements (Zionist Organization of America, New York). This work lead to Learsi’s involvement with more current political issues and in 1920 he wrote a book for the Committee on Protest Against the Massacre of Jews in Ukrainia and Other Lands, of the American Jewish Congress, titled The massacres and other atrocities committed against the Jews in southern Russia: a record including official reports, sworn statements, and other documentary proof. This was followed by a political text on the Zionist movement (His Children, published by The Jewish Welfare Board in New York in 1925), the same year that Kasriel the Watchman and Other Stories appeared.

His prolific work over the ensuing four decades appeared in a wide range of media, including newspaper articles and editorials, magazine articles, educational literature, stories, compendiums of Jewish humor, anecdotes, tales, and Hassidic ballads, nonfiction books and biographies from Jewish history (including, in 1949 -- one year after the founding of the modern state of Israel -- Israel: as History of the Jewish People), accounts of Jewish military history (these appeared, not surprisingly, in the late 1930s and early 1940s), many plays for both adults and children, and even one musical score (“Hail the Maccabees!” in the 1930s). Learsi is perhaps best known, however, for two publications toward the end of his career, both major studies of the Zionist movement in America and abroad: Fulfillment: the epic story of Zionism (Cleveland: World Publishing Company, 1951) and The Jews in America, a history (New York: World Publishing Company, 1954). Given the nature of events on the world stage in the decade following the founding of the modern state of Israel in 1948, the publication of these two books was greeted with a heightened degree of scrutiny in the press. Many reviewers took Learsi to task for his unapologetically partisan slant in his histories. A good example of this may be seen in a review of Fulfillment written by fellow Zionist Robert Weltsch in 1952:

Mr. Learsi's book is well written, carefully composed, and it sums up a wide range of relevant facts, moving with intelligence and skill over a subject of immense complexity; its language is mostly moderate and restrained, and the general reader can get from it a good picture of the historical and spiritual forces which created the mystique of Zionism and the modern Zionist movement.

But, like most histories of Zionism, this book is mainly a piece of propaganda, and this harms its value as a historical work. Mr. Learsi tends to accept uncritically, sometimes even naively, the official Zionist version of history; he sees all opposition as expressing a sinister malevolence, and thus he misses the essential drama of the story, which was—and remains—most often a story, not of right against wrong, but of opposed rights.

Information on the publisher of Kasriel is much easier to come by, particularly because the organization -- the Jewish Publication Society -- still exists. Founded in 1888, the nonprofit JPS was originally dedicated to providing second-generation Jewish Americans with English-language books about their heritage and their history. It has since expanded to include a larger audience and a broader range of books in different genres and on different topics. Most famously, JPS publishes a text of the Tanakh that is accepted as standard by most scholars, synagogues, rabbinical schools, and Christian seminaries.

My copy of Kasriel the Watchman and Other Stories is hardcover, its boards decorated with red cloth bearing repeated diamond-shaped pictures (an old, bearded man in a hat, alternating with a cityscape with a star or sun overhead). There are inconsistencies between each image on the decorated cloth, revealing that they were each individually drawn rather than stamped. The spine is black cloth; some dealers listing this book claim that titling is visible (usually faded) on the spine, but mine has no trace. The pages measure 12.5cm x 18.75cm and are of a heavy but not particularly expensive stock. It is in octavo format (some dealers list it erroneously as duodecimo) and the pagination runs [1]-311. The preliminaries (title page and copyright; blank conjugate with frontispiece; dedication and thanks; contents] are unnumbered, as is the final blank flyleaf conjugate with the rear pastedown.

The book is in rough condition: the spine is quite tattered and the corners of the boards are bumped; the first three leaves of the preliminaries are loose; some page corners are dog-eared; slight water-staining occurs throughout (never interfering with text, though); in some openings the spine is splitting slightly; and, most oddly, there are some ancient, dried crumbs of bread scattered on the first page of the story “The Beggar’s Feast”. The book has clearly been well-read over the years. Despite this, however, there is little evidence of owners’ writing in the book (perhaps not surprising; there seems little reason for a reader to mark up or annotate in any meaningful way a collection of stories such as this -- as opposed, for example, to books such as textbooks, scholarly works, nonfiction, religious books, etc.).

The only previous owner’s marking occurs on the recto of the blank leaf between the title page/copyright and the frontispiece plate; the name “Morton Margolis” is penned in faint blue ink and blocky letters in the upper right corner, and beside it there is an excellently drawn portrait of an old bearded man in a flat (Russian?) hat, inked in watery green ink (perhaps watercolor paint?). I have no verifiable lead on who this man might have been, though there was a late Morton Margolis who was a professor of humanities at Boston University and also a practicing artist. According to his November 1990 obituary in the Boston Globe, Margolis specialized in the connections between music, art, and literature and was known for “enliven[ing his] lectures by playing...on the piano.” If this man is the same Margolis who owned my copy of Kasriel, his delicately detailed painting on the blank leaf certainly does offer a connection between art and literature -- in a very unique and personalized way.

Evidently Learsi obtained the material for his collection of stories from tales he had heard as a child (the dedication reads: “This medley of childhood memories I dedicate to my mother.”), and so the target reader was likely young Jewish boys of the post-World War I generation (though the stories themselves would hearken back to a pre-World War I Jewish community in America -- the time and place when Learsi was a child). There is also a special publisher’s note following the dedication that I have been unable to decipher: “The Jewish Publication Society of America is indebted to NATHAN H. SHRIFT, of New York, for aiding in the publication of this volume.” Who “Nathan H. Shrift” was I cannot tell; my suspicion is that, because the JPS was a nonprofit organization, Mr. Shrift was a benefactor who fronted the capital for the publication, but I have no evidence of this.

Included in the book are five illustrative plates inserted into gatherings on semi-glossy stock (including the frontispiece); at least one dealer online lists another copy of this edition with seven plates, which seems to suggest that two have fallen out of my copy at some point (the perils of illustrative plates that are not integral to a book’s gatherings). The artwork is fairly standard, representational black-and-white drawings that depict moments from the stories into which they are bound. These pictures are signed “R. Leaf”; I assume that this is Reuben Leaf, a prolific New York artist who taught an Arts and Crafts Group at the famed 92nd Street Y in the 1930s and whose illustrations accompanied many Jewish American books from the 1920s through the 1950s. Leaf also published his own art books through his studio imprint (most famously, his Hebrew Alphabets: 400 B.C.E. to Our Days in 1950 -- a work of beautiful graphic art but that received some scathing notices for including a large amount of inaccurate scholarship on its subject).

Learsi has organized his book into five groups of stories; each of the first four groups centers on one or two recurring main characters (“Kasriel the Watchman”, “Perl the Peanut Woman”, “Benjy and Reuby”, and “Feivel the Fiddler”) and the final group consists of varied “Phantasies”. The structure is broken up slightly by the occasional inclusion into these groups of unrelated miracles and legends from Jewish lore. Overall, the collection includes thirty-one stories. The final story, dedicated to someone named “David Emmanuel” (possibly a euphemism for the Jewish people?), is perhaps the most overtly political Zionist tale in the book.

Titled “The Severed Menorah: A Glimpse of the Great Tomorrow”, it tells of two Polish brothers (named, of course, David and Emmanuel) who go off to Russia to become scholars of Hebrew law. Their mother insists that they take the family menorah with them and pawn it for money to live on, but they cannot bring themselves to sell such a sacred object, though they take it with them for their mother’s sake.

Soon after, a great tempest of anti-Semitism sweeps through Europe and in the violence the two brothers are separated -- each taking with them a separate piece of the menorah (one the base and the other the branches). When the fighting finally comes to an end, the surviving Jews from across the globe make their way to the “Ancient Land” and to build a home for themselves. Many years go by until, one day, an elderly Jew from America goes to visit this new land. He eventually finds himself in a synagogue where an old rabbi is debating the law with his fellows; the tourist discovers to his surprise that their menorah consists only of branches inserted into a wooden base for support. From his bag, the man withdraws the missing base of the old menorah and so the two brothers -- like the menorah and like the Jewish people -- are finally united once more. An appropriate tale, I felt, at the end of this Hanukkah holiday. Tzeth'a Leshalom VeShuvh'a Leshalom.

I am very moved and surprised to come across this early trace of my father, Morton Margolis, as budding artist and book lover. Yes, Tarquin's ID seems correct. MM's youthful, experimental ex-libris signature bears a resemblance to his mature one. He was a fine musician and artist--this green wash portrait resembles what he would have seen from his Aunt Sarah (Tipograph) a good painter herself and his first "art teacher", who painted scenes of shtetl life from her native Lithuania. He must have been in his early teens when he signed this and did the painting. Yes, he taught at BU, kept up his intellectual life, music and painting and through his retirement until his death in 1990.

ReplyDeleteThank you very much,

Nadia Margolis

I also bought recently this book, in a very good condition. The title is clearly visible on the spine, and there are 8 (not 7) pictures. On the Internet, I found some information about the author, Rufus Learsi, aka Israel Goldberg (1887-1964). Just as the author of the first blog, I could not find anything (except of this blog) regarding Nathan H. Shrift, who aided in the publication. My copy is also signed. In faded purple ink, it says :

ReplyDeleteBernice Cristol, 1022 N. Mulberry Ave, San Antonio Texas Aug. 1st, 1926

Surprisingly enough, I was able to find some information regarding the first owner of the book. She was just 10 when the book was signed: born in 1916, died at 94 in 2010, a devoted wife of 69 years of a renowned radiologist, Dr. Joseph Selman (1915-2010), mother of four and philantropist...

Prof Morton Margolis was my favorite teacher at Boston University during the 70's!!

ReplyDelete