This week’s book is a fragile, well-worn paperback of Edwin Booth’s Prompt-Book of Hamlet, as edited by the contentious Gloucester, MA-native author, poet, journalist, and drama critic William Mercutio Winter (1836-1917; shown here in 1916) (contentious because of his constant attacks on the realist movement within the modern theatre, a style that he saw as “rank, deadly pessimism... a disease, injurious alike to the stage and to the public”). As I’ve mentioned previously, these acting editions of modern productions of Shakespeare plays are useful for recuperating how previous generations have interpreted Shakespeare -- though they’re essentially useless as objects of textual study or for understanding their original early modern theatrical context.

Booth (1833-1893; an early photo of him in the role of Hamlet...sitting in the same kind of chair Winter posed in!) -- older brother of the more infamous actor John Wilkes Booth -- came from trans-Atlantic theatre royalty and was one of the most celebrated actors of the nineteenth century American stage; his performance in many leading Shakespearean roles helped crumble the British presumption that non-English actors could not grapple with the great playwright’s subtleties of language and nuances of character. In particular, his portrayal of Hamlet was lauded throughout his career, taking him to stages across the U.S. and U.K. -- according to most accounts, he played the role of the Danish prince more often than any previous actor on record. The relationship between Booth and Winter was professional (the latter wrote reviews of the former’s productions, but also penned a biographical article on him for Harper’s in June 1881 and, upon the actor’s death, published a book-length biography, The Life and Art of Edwin Booth for MacMillan and Company in 1893). More relevant for my purpose, however, was the series called The Prompt-Book, which Winter edited for the firms of Lee & Shepard (41 Franklin Street, Boston, and, at this time, still struggling to recover from bankruptcy following a calamitous fire in 1875 and the Panic of ‘73) and Charles T. Dillingham (678 Broadway, New York, formerly of Lee & Shepard). This series presented, in “uniform volumes”, performance texts of Booth’s most popular productions, including Shakespeare’s Merchant of Venice, King Lear, Othello, Macbeth, Much Ado About Nothing, Richard II, Richard III, Julius Caesar, Henry VIII, and “Katharine and Petruchio” (Taming of the Shrew).

My copy is of the third edition of the Hamlet prompt-book; all three editions appeared in 1878, though -- unlike the previous two -- this one was published by the New York firm of Francis Hart & Company (63-65 Murray Street, better known as the publisher of Scribner’s Monthly). Subsequent editions followed from Penn Publishing (Philadelphia) in 1896 and 1909. Presumably Booth derived some kind of income from Winter’s editions; he certainly needed it, since in 1874 his custom-built theatre at 23rd Street and 6th Avenue was shuttered and his fortune essentially vanished with it (Booth recovered and continued playing to great success until his death; his last appearance in the role of the young prince Hamlet was in 1891...at the age of 58). The copy is bound in paper covers with a cloth spine; the spine has faux stitching where it joins to the front and back covers, probably to imitate the look of the typical theatrical prompt-book of the day (the binding is actually held together with a series of metal staples). The front cover bears the title, along with a crest showing a raven on a branch; the back cover bears the Medusa-head logo of Francis Hart & Company. The pages are of a dull stock, though heavy enough to be written upon with ink and not show bleed-through; they measure 12cm x 17.25cm.

The text of the play itself only appears on the recto of pages -- a practice that essentially doubles the size (and hence paper and composition cost) of the book; the facing verso was perhaps left blank to allow space for amateur thespians to make their own notes for productions. The pagination starts on the title page and runs [1]-136. An unnumbered leaf before the title page is blank on the recto and bears a list of the other titles in the series on the verso; at the back there are three blanks (the pastedown on the back cover is coming up on my copy, making it seem as if there is a fourth blank leaf). The gatherings are in quires of eight, though I would hesitate to actually call the book an octavo. The condition of my copy is fairly poor; the interior state is acceptable, but the front cover is quite loose and most of the cloth spine is disintegrated. The only markings are some basic arithmetic, in a pencilled late nineteenth-century hand, on the verso of the second blank leaf at the back and a faint inked inscription on the recto of the first blank:

A. J. Hendrickson

From Ellis Archer

I’ve found a few matches to these names, but, regrettably, nothing with the two together and certainly nothing that absolutely confirms who these people might have been.

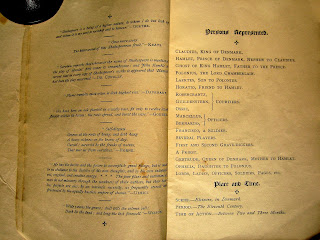

Besides the play itself, the edition includes a a number of epigraphic quotes about the play from various sources, a dramatis personae list and setting description, and a brief preface (pp. 3-5; dated “New-York, Feb. 7th, 1878) in which Winter explains some key points about the play (particularly the rich ambiguity surrounding Hamlet’s “madness”), about Booth’s cuts (he itemizes the major excisions and says a few things about why the passages were taken out -- usually being for purposes of clarity), and about the edition itself. At the back of the book, Winter includes an appendix of brief essays on the play for “theatrical students”. These include one by Winter on “The Character of Hamlet” (pp.127-8), another by him on “Facts about Hamlet”, mostly concerned with dating and its original theatrical context (pp. 128-30), a selection from Collier’s Shakespeare Library, Vol. I, providing an extract on “The Original Story of Hamlet” (pp. 130-2), a selection from Guizot on “The Madness of Hamlet” (p. 133), comments from Edward Dowden on the structure, “Incidents and Scheme of Hamlet” (pp. 133-4), two selections -- one from Coleridge and one from Ulrici -- on “The Key-Note of Hamlet” (that is, the most important qualities of his character; pp. 134-5), and finally another essay by Winter on “Time, Age and Persons of Hamlet (pp. 135-6; Winter notes that Hamlet is 30 years old -- which is debatable -- and at the time this book appeared Booth himself, still playing the role, was 45).

In terms of the text itself, one of the qualities for which Booth was celebrated was, unlike most contemporaneous performers, he largely stuck to the text of the play as it appeared in the early editions of the seventeenth century. This should be qualified, of course, by noting that he did so in comparison to his contemporaries -- many of whom made severe and grossly radical, unwarranted changes to the texts.

Booth’s text for Hamlet is not without its alterations: large portions are cut (about 1,000 lines by Winter’s count) for a number of reasons (“[they] might prove tedious in the representation.... [they] momentarily arrest the action of the piece....[they] are but the descriptive repetition of action that has already been shown...[they] do but amplify and reiterate ideas that have previously been made sufficiently clear for the practical purposes of the stage”). A few lines and passages have been shifted about or transposed and sometimes words have been slightly altered (“but never to the perversion of the meaning”, Winter somewhat idealistically observes). More subjectively, “[c]oarse phrases have been cast aside, or softened, wherever they occur” -- which sounds dangerously close to the infamous brutalizations of Dr. Bowdler and others. Perhaps the most substantive changes to the text appear, not surprisingly, in the way of stage directions -- this is, after all, a “prompt-book”. Booth’s directions are quite full and detailed, indicating precisely both the settings for the scenes and, down to their position on the stage, the movements and business of the characters. It would be quite a simple task for an enterprising director to re-create the Edwin Booth Hamlet from Winter’s edition of it (though one recurring direction, "Picture", appearing at the end of every act, might need to be puzzled out). If only one of the early seventeenth-century texts were so helpful in re-creating how Shakespeare’s production of Hamlet was staged!

To conclude this week’s post, I’d like to return to my trip to Princeton, to the underground bookstore where I acquired this piece of nineteenth-century American theatre history. The experience offered up one more reason I enjoy shopping in used book stores rather than new book stores. In new book stores, the price that is stamped on the book is the price that you have to pay -- even if you think it is an inaccurate reflection of the book’s value (which seems to be true more often than not). In used book stores, the price is almost always negotiable -- fine points such as the seller’s sense of the buyer’s interest in or commitment to the book, the seller’s compassion, the length of time it has been sitting on the seller’s shelf taking up space (one reason I like to return to some stores repeatedly) or, of course, the condition of the copy, can greatly shift the price because they do actually shift the book’s value (I’ve written previously on the three points that make up a used book’s value: importance, scarcity, and condition).

There was no price penciled inside the front of this copy of Booth’s Hamlet, so I presented it to the owner of the store and inquired as to what he thought was fair for it. He looked at it -- eyeing the extremely loose front cover and deteriorated spine -- looked at me and shrugged, “You can just take it. We can’t sell something in that condition.” I’m not sure who would absolutely demand that a copy of this obscure and somewhat unimportant book be in ideal condition, but for my own desires I recognized it as something that I wanted in the Bookcase -- despite its sadly drooping cover.

On the way out of the store -- as we walked past the antiques shop with the hyperbolic prices -- I thought of what my brother had originally warned me about shopping in Princeton. There's almost always a difference between the monetary value of a book and what it's worth -- in a non-cash sense. You don’t need lots of money to be a satisfied book-collector; all you need, really, is sense. Especially a sense of what is valuable to you.

No comments:

Post a Comment