Recently in my class we had a discussion about the idea that “everything is a text”. We came around to the concept that pictures are a kind of text because they encode meaning, have their own kind of "rhetoric", and are meant to have a specific kind of effect upon the “reader/viewer”. This week’s book is a fine example of how narrative art in a book (often seen in books for younger readers or children) can tell a complete story, even if the reader can’t understand the words.

The book is a slim hardcover edition of Wilhelm Busch’s classic German verse tale for children Mar und Moritz eine Bubengeschichte in sieben Streichen [“Max and Moritz: A Boyish History in Seven Tricks”]. This edition was published in Munich by Verlag von Braun & Schneider. There’s no date, but the title page does indicate that this is a copy of the sixty-third impression. It was first published by Braun & Schneider in 1865 and remained one of the firm’s best-selling titles into the 1950s. Judging from the book’s appearance and construction, I suspect that my copy dates to approximately 1900-1910.

Max and Moritz quickly became the best-known comic characters from Germany and their misadventures were translated into over thirty languages. Perhaps most famously in America, they served as the model for Rudolph Dirks’s long-running comic strip “The Katzenjammer Kids”. Busch (1832-1908; seen here in an 1894 self-portrait), credited as one of the pioneers of modern comics, wrote and illustrated many other verse satires and comics (and, as a painter and sculptor, produced over 1,000 pieces of art), but Max and Moritz remains today his best-known and most widely read work. It is so familiar in the collective knowledge of German-speaking countries that the image of Max and Moritz’s smug faces (below) is still often used as a kind of shorthand for “mischief” in marketing and other forms of popular culture. More bizarrely, Wernher von Braun named the first two test rockets in the A2 project (1934) Max and Moritz -- a tribute to a much more violent and disturbing form of "mischievousness".

The pages measure 14cm x 21.5cm and are of a firm stock. Only the recto of each leaf is used for the book’s content; the versos are all blank. Collationally, the book may be described as 8o: [#] 18-77: $2. Each gathering is bound individually with three metal staples. The initial blank flyleaf is conjugate with the front pastedown; it looks as if the final leaf of gathering 7 was used as the rear pastedown. The initial blank, title page, and one-page Vorwot [“Foreword”] are unpaginated; pagination begins with the “First Trick” on the next page and runs [1]-53 -- only the rectos are numbered, however, since the versos are blank. The book is bound in paper-covered boards (some chipping, but nothing severe) with black-ink title and decorations on the front and publisher’s advertisements on the back; the spine is quite worn and some of the cloth beneath the paper covering is showing through.

As the title implies, Busch’s wildly popular narrative relates, in rhyming couplets, the tale of Max and Moritz, two young boys who unleash a sequence of seven tricks, or pranks, upon the unfortunate and unsuspecting adult members of their village. In the end, however, the little brats do get their (shockingly violent) punishment.

The contents are:

Foreword, [no number]: introducing the boys and cautioning children not to emulate them.

First Trick, [1]-8: the boys snare old Widow Tibbets’s three prize hens and rooster and hang them; as they hang, the hens drop some fresh eggs.

Second Trick, 9-15: using fishing rods, the boys reel the cooking chickens up the chimney and eat them; the old woman blames her dog, whom she soundly beats with a wooden spoon.

Third Trick, 16-22: the boys lure the sartorially obsessed Mr. Buck to chase them across a bridge over a river; they’ve weakened the bridge, however, and he falls into the freezing water, only escaping by holding onto the tails of some geese as they fly away; at home, his wife presses a hot iron against his body to dry him out.

Fourth Trick, 23-29: pompous school-teacher Master Lämpel loves his pipe, so the boys fill it with gunpowder and blow his face off.

Fifth Trick, 30-38: Max and Moritz gather as many beetles as they can carry and dump them into Uncle Fritz’s bed; he awakes in horror and crushes the pests underfoot.

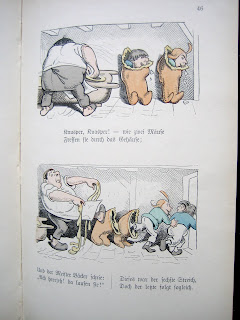

Sixth Trick, 38-46: an attempt to climb down the baker’s chimney to steal cakes goes awry and the boys end up in a vat of flour; in revenge, the baker rolls them in dough and bakes them in the oven.

The resilient imps survive and escape by eating their way out of the crust from the inside.

Seventh Trick, 47-52: having learned nothing from their close brush with fate, the boys cut a slit into a farmer’s corn sack and it all pours out as he walks away; irate, he grabs the two and takes them to the mill where they are ground into pieces.

The bits of Max and Moritz are tossed aside (“Here you see the bits post mortem, / Just as Fate was pleased to sort ’em") and the miller’s ducks gobble them up. “The gruesome ending,” notes one scholar of German children’s literature, “is in keeping with the strict Prussian-era pedagogy that emphasized ethics, duty, discipline, and obedience.”

Conclusion, 53: the town’s residents jubilantly celebrate the just punishment of the two little terrorists.

For a full version, the Department of Foreign Languages at Virginia Commonwealth University has a website with the German text, English translation, and links to more resources, including the Wilhelm Busch Museum.

When I first browsed through the book, I was completely stumped by the German and could not understand a word of the poetry. However, Busch’s color art is so vivid and alive, and appears so precisely at key moments in the Tricks, that a very clear understanding of the narrative can be obtained simply by scanning over the illustrations.

In closing, I’ll end this post with the English translation of the start of the Fifth Trick, which I think offers an excellent bit of advice:

If, in village or in town,

You've an uncle settled down,

Always treat him courteously;

Uncle will be pleased thereby.

In the morning: "Morning to you!

Any errand I can do you?"

Fetch whatever he may need,-

Pipe to smoke, and news to read;

Or should some confounded thing

Prick his back, or bite, or sting,

Nephew then will be near by,

Ready to his help to fly;

Or a pinch of snuff, maybe,

Sets him sneezing violently:

"Prosit! uncle! good health to you!

God be praised! much good may't do you!"

Or he comes home late, perchance:

Pull his boots off then at once,

Fetch his slippers and his cap,

And warm gown his limbs to wrap.

Be your constant care, good boy,

What shall give your uncle joy.

No comments:

Post a Comment