I usually try to do my blogging on Sunday mornings -- a quiet time of rest and relaxation after a long week of work. This week's was written a few days ago, though, since this weekend has been mostly spent up in beautiful Vermont attending a beautiful wedding.

Leisurely Sunday activities that were both enjoyable but also informative also figured into the life of the American writer Samuel Clemens, or “Mark Twain”. Through most of his life, every Sunday Twain would collect, sort, add, and organize material in a vast library of scrapbooks -- blank books into which he pasted notes, news clippings, photos, letters, postcards, envelopes, checks, book reviews and other materials (often about his life and career), and indexed in the front for quick and easy reference.

Mark Twain was many things -- humorist, publisher, author, entrepreneur, pseudo-Shakespeare scholar -- but one of his great passions was science and inventing. He was good friends with Nikola Tesla and acquaintances with Thomas Edison. Twain himself patented three inventions: the first was “An Improvement in Adjustable and Detachable Straps for Garments” (meant to replace suspenders -- the idea never caught on), the second was a history trivia game (it did not sell well), and the third was “An Improvement in Scrap-Books”. This last was the only invention off which Twain made any money.

Twain applied for a U.S. patent for his scrapbook on May 7, 1873 and secured it on June 24 that year. However, he delayed hiring a firm to manufacture the book until after he had obtained a U.K. patent on May 16th, 1877 and a patent in France two days later. In 1877, Twain hired his friend, the New York printer Daniel Slote (the wisecracking and mischievous “Dan” of Twain’s Innocents Abroad), to produce and sell the scrapbook. Between August and December 1877, Slote sold over 26,000 units, grossing Twain an astonishing $1,072 (approximately $22,250 in modern currency).

Thus convinced that his invention was a success, on April 23, 1878, Twain trademarked the name “Mark Twain’s Scrap Book”. Slote’s business, however, was on the brink of failure and the publisher had to obtain a $5,000 loan from Twain to keep up production of the scrapbook; Twain, a few years later, spent another $20,000 to buy 800 of the 1,000 shares that Slote made available to the public to stay in business (on this affair, see Ron Powers’s Mark Twain: A Life, pp. 435-6). Slote took out a sizable advertisement in The Publisher’s Weekly Christmas edition of 1878, promoting the scrapbook as “The Holiday Gift for 1878”. The editors of Publisher’s Weekly concurred: “A scrap-book is a first-rate Christmas present,” they offer, “particularly in the present rage for scrap-book pictures. And Mark Twain’s Scrap-Books, ready gummed for any purposes of a scrap-book, as manufactured by Daniel Slote & Co., are said to be ‘first-ratest’ of all” (xiv:687).

The Dial for November 1883 lauded the book as “a universal favorite” that “bids fair to supersede all other Scrap Books” (177):

It is a combination of everything desirable in a Scrap Book. The convenience of the ready-gummed page, and the simplicity of the arrangement for pasting, are such that those who once use this Scrap Book never return to the old style.

To travellers [sic] and tourists it is particularly desirable, being Scrap Book and Paste Pot combined. In using the old-fashioned Scrap Book, travellers have hitherto been compelled to carry a bottle of mucilage, the breaking of which among one’s baggage is far from pleasant. This disagreeable task is avoided by the use of Mark Twain’s Scrap Book.

The ungummed page Scrap Book is at times of no service whatever, if paste or mucilage be not at hand when wanted. With a Mark Twain no such vexatious difficulty can possibly occur.

The “Editor’s Literary Record” in Harper’s Monthly (June 1877) also praised the product:

Mark Twain’s Scrap-Book is what Burnand would call a “happy thought.” It saves sticky fingers and ruffled pictures of scraps. It is simply the application to a scrap-book of the principle long in vogue in the self-sealing envelopes. The pages are prepared with gum, and are prevented from adhering by tissue-paper between the sheets. As the scrap-book is used, the tissue-paper is taken out, the page has simply to be moistened, and the scrap or picture pressed on. Neither paste nor gum-arabic is required by the user. It is a capital invention, especially for children, to whom the ordinary scrap-book is a never-ending source of delight. [55:149]

Some other reviews, though favorable, strike a rather odd tone. The Norristown Herald, for example, urged that “No library is complete without a copy of the Bible, Shakespeare, and Mark Twain’s Scrap Book.” The Danbury News ran a particularly peculiar favorable review:

It is a valuable book for purifying the domestic atmosphere, and, being self-acting, saves the employment of an assistant. It contains nothing that the most fastidious person could object to, and is, to be frank and manly [?], the best thing of any age -- mucilage particularly.

Why praising "mucilage" is considered "manly" is a mystery to me.

But not all reviewers were delighted with the scrapbook. “Mark Twain’s latest joke is a scrap-book of his own invention, gummed, ready for use,” sneers the English quarterly Westminster Review (January 1879), “A very good joke it is” (New Series, 55:297).

Mockery from across the pond notwithstanding, by 1901 Twain had developed nearly sixty different styles and types of his popular scrapbook and new versions were still being sold at least as late as 1912 (despite the success of the scrapbook, Slote & Company -- in the hands of Dan’s widow, Sarah, after his death -- dissolved in bankruptcy in 1889 and Twain shopped out the manufacture of his scrapbook to other firms). According to some commentators, Twain may have made more money off this one invention than his prolific writings, though Harriet Smith and Lin Salamo, in Mark Twain’s Letters, suggest it merely provided “a modest but steady income” (v:145). Estimates put Twain’s total lifetime earnings from the sale of his scrapbooks at around $50,000 -- or around $891,500 in modern currency.

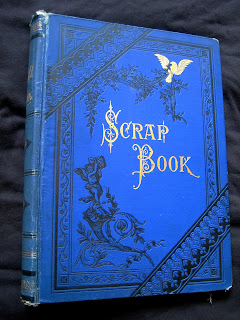

My copy of the Twain scrapbook was, as with all authorized Twain scrapbooks, published by Daniel Slote & Company, makers of blank books and journals based at 119-121 William Street, New York. As an avid scrapbooker himself, Twain knew what features would make the best possible scrapbook: two columns of gummed adhesive on each page of heavy, gray stock (“Use but a little moisture,” read the instructions, “and only on the gummed lines. Press the scrap on without wetting it.”); four perforated pages of tissue interleaved between the numbered pages prevented the gummed surfaces from sticking to each other; four pages of blank lines with alphabetical headings for the index at the front (including, for some indiscernible reason, three sections labeled “M”); a folding envelope pasted on the inside back cover (facing in toward the gutter) for the quick accumulation of items before organizing them and pasting them into the book. The binding is blue cloth over boards, with ornate black tooling and gilded decorations. Each gummed page bears a page number in blue ink stamped in the upper outside corner; there are one hundred pages, not including the four for the index, plus one blank flyleaf.

The scrapbook has seen use: several pages (most early in the book, a few scattered later, and several at the end) have newspaper clippings that seem to span quite a long period of time (the earliest seems to be from the nineteenth century and the latest from the 1950s).

The remaining scraps are remarkably eclectic, ranging from a story about a fatal shipwreck in a blizzard off the east coast to the capture of a “mermaid” off Camden, New Jersey, to the restoration of an old blast furnace in Trenton, New Jersey. Most of the clippings are from New Jersey papers, though it seems a few are from New York and some from Massachusetts. The person who collected them seemed to have a slightly morbid interest in death and the afterlife, and there are also a fair number of religious pieces.

The only handwritten marginalia is a note in blue pen on the scrap of the story about the blast furnace, labeling it as from the Newark Evening News on January 27, 1958.

Though only a few pages bear scraps, all of the tissue pages have been removed and some of the gummed lines have scraps and scars from where clippings were once adhered. Why someone would pull out most, but not all, of the collected scraps is a mystery. Perhaps they intended merely to clean out the book and reuse it for their own purposes. Or perhaps a more personal reason underlies their decision to expunge nearly one-hundred pages of collected memories and history.

Thank you for this posting. It solved a big mystery for me. I have been working on transcribing the news clippings in an old scrap book (a Mark Twain) and wondered why the person did not label any of the clippings. Well it seems the book we have is missing the Index pages and we had no idea that they ever existed. Now we know that somewhere in Wisconsin in some old dusty attic are the index pages for the scrap book we have. My son bought the book at an old book store in Chicago and we have no idea where it came from except the clippings seem to point to Wisconsin in the years 1880 to 1905.

ReplyDelete