"Let your bookcases and your shelves be your gardens and your pleasure-grounds. Pluck the fruit that grows therein, gather the roses, the spices, and the myrrh. If your soul be satiate and weary, change from garden to garden, from furrow to furrow, from sight to sight. Then will your desire renew itself and your soul be satisfied with delight." - Judah Ibn Tibbon

Sunday, October 31, 2010

Happy Halloween!

Sunday, October 24, 2010

Samuel Hall: Printer-Patriot [part 2]

Since I was back in Salem for the weekend, I thought it would be appropriate to feature another one of my Samuel Hall imprints this week. As I’ve mentioned previously, Hall was the first printer in my hometown of Salem and part of my goal as a collector is to add as many of his Salem publications (particularly from his 1768-1775 tenure in the town) to my bookcase. This was one of his pamphlets from the last few years of his first, pre-war time in Salem. It's sobering to think that all of the equipment on which this imprint was printed -- the presses, the tools, the type -- as well as any unsold copies of it still in the shop were all lost to the fire that destroyed Hall's building in 1774.

The half-title of this pamphlet reads:

Mr. Webster’s / Two / Discourses, / Upon / Infant-Baptism, / and the / Manner of Baptizing.

The text on the half-title is surrounded above and below by floral line device, not unlike that seen on Hall’s later imprints as well (though a bit more simple in design). There is an elegant brown pen inscription in the upper outside corner: S. Livermore (not a terribly common name in the period; this possibly may have been the famed legal writer and politician Samuel Livermore of New Hampshire). The only other evidence of readership (aside from smudges and wear) is a worn piece of an old newspaper used to mark a place between pages 18 and 19; I cannot, from the text, determine what paper the piece is from, or the date, but a reference to “American vessels” indicates that it was probably post-1776.

A Frankenstein-like stitching repair runs across the mid-page of the half-title. A similar repair using the same kind of white thread was done on pg. 31/2 down the entire length of the leaf. The only other major damage that affects the text is on the final leaf, which has become quite torn and folded from its exposure.

The full title of the pamphlet reads:

Young Children and Infants declared by Christ Members of his Gospel Church or Kingdom: And, therefore, to be visibly marked as such, like other Members, by Baptism. And, Plunging Not Necessary. Two Discourses, Delivered September 20th, 1772. To the West Congregation in Salisbury, and, Afterwards in several neighbouring Parishes. Published at the Desire of the Hearers.

By Samuel Webster, A. M. Pastor of a Church in Salisbury

Salem: Printed by Samuel and Ebenezer Hall. 1773.

In addition, the title-page includes two quotes from patristic commentators (Justin Martyr and Iraeneus) along with glossarial notes on their technical terms. The pamphlet was subsequently reprinted, with no alteration to the contents, by T. and J. Fleet of Boston in 1780.

As with nearly all pamphlets, it was never bound; instead it was stab-stitched through the face of the pages (binding involves sewing outward through the spine fold -- a fine, but important, distinction). Interestingly, the stab-stitching was added after the gatherings had been sewn through the face of the pages with a criss-cross pattern; after this was done, a brown piece of heavy paper was folded over the spine to protect it and then the stab-stitching was done through this piece of paper to hold it all together. I’ve never seen something like this before and I wonder if it was done by Hall or a later seller or owner.

The paper is a soft linen stock typical of the period, but quite foreign to the modern touch; it feels much more like cloth than paper. 3cm vertical chain lines run down the pages; there are no watermarks. The pages measure 14cm x 23cm; I say “approximately” because a good deal of bumping and chipping to the edges of the paper makes it difficult to say for certain. The contents are: [i], half-title and blank verso; [iii], full-title and blank verso; v-vi, Preface to the Reader; 7-54, the contents of the “Two Discourses” (not divided, but run together as one long essay).

As was typical with Hall’s imprints at this time, there are no running-titles; the header only provides the page number, centered and surrounded by parentheses (there are no errors in pagination). Its collation may be described as 4o: [A4]-G3: $1. The missing leaf of the final gathering is not odd and may have once been present as a blank for protecting the exposed text on the verso of G3. The catchwords across the sheets are: often | an | could | runs; | And | Con- [Consider]. With the exception of the final error, there are no errors in either these catchwords or those internal to the gatherings. The type is very clean and simple, showing no substantial damage or ostentatiousness; even the footnotes are all marked with a simple asterisk (a change from his later publications, in which he used a wide variety of symbols). There were no problems with distribution or alignment and only the occasional, very minor inking problems (such as the occasional double-register around page numbers).

The pamphlet’s subject was the contentious question of whether or not children and newborns should be baptized (as most Protestant faiths believed) or whether baptism could only be undertaken by an adult who was fully aware and able to make the choice to be baptized (the position of the Baptists). The schism was a pronounced one and a flood of literature on the subject swamps the shelves of theology libraries; it came to prominence as a problem for debate in the early years of the Reformation in Europe and spread rapidly as a core religious problem. Though there was actually a brief lull in the scope of the debate in the mid to late eighteenth century -- when Webster wrote and delivered his sermon -- it came back in force in the nineteenth century, particularly in the so-called Second Great Awakening in America.

Samuel Webster (1718-1796) was one of ten children of Samuel Webster Senior and Mary Kimball. He rose to prominence in the community of Salisbury and on December 24, 1766 he married Susanna Juell (Jewell) from the neighboring town of Amesbury. He held a masters degree by 1772 and a doctorate by 1792. Webster served as the pastor of the West Church of Salisbury for 55 years at the time of his death. The West Church (better known as the West Parish) had formed in 1716 when residents of the Rocky Hill area voted to split from the town’s only church and form their own (a move undertaken for political and tax-paying purposes as much as convenience or theology).

Webster was a highly prolific writer and published a number of his sermons through Samuel and Ebenezer Hall, including a sermon on “Ministers labourers” given at the First Congregational Church of Temple, New Hampshire on October 2, 1771. He also published sermons on a range of theological, social, and even military topics through Edes & Gill of Queen Street in Boston. Some of his more well-known publications in the period include An Evening’s Conversation Upon the Doctrine of Original Sin, Between a Minister and Three of His Neighbors Accidentally Met Together (Boston: Green & Russell, 1757) a critical retort to Danver pastor Peter Clark’s earlier scriptural exegesis in A Summer Morning’s Conversation (Boston: Edes & Gill, 1759). He also dabbled in natural history and early science -- especially geology -- publishing an article on an “oil-stone found at Salisbury” in the Memoirs of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1783.

In his time, however, Webster was perhaps best known for his work and writing as both a supporter of the break from England and an early abolitionist. On July 14, 1774, on a day “set apart for fasting and prayer, on account of approaching public calamities”, he delivered to his congregation a pro-revolution sermon on “the misery and duty of an oppres’d and enslav’d people”, the print version of which became (after An Evening’s Conversation) his most frequently re-published text (Boston: Edes and Gill, 1774). In his widely-read Earnest Address to My Country on Slavery (1796), Webster republished a sermon he delivered to the Massachusetts legislature on May 28, 1777 (in the midst of the War; this was not the only time Webster was called upon to deliver a sermon to the Great and General Court). In his text, he urged that his fellow Americans, “for God’s sake, break every yoke and let these oppressed ones go free without delay -- let them taste the sweets of that liberty which we so highly prize and are so earnestly supplicating God and man to grant us: nay, which we claim as the natural right of every man” (37-8). It is little surprise that such a politically passionate, pro-revolution man of the cloth should chose to publish with Hall, who was a likewise politically passionate, pro-revolution man of the press.

In 1776, only a few short years after delivering his sermon on child baptism, Reverend Samuel had the chance to put his theories into practice. Twice. On August 19 of that year he performed the double-baptism for his newborn twin children: Betty and John.

Sunday, October 17, 2010

The Rules for the Game of Matrimony (According to Hoyle)

A couple of weeks ago -- before the hectic weekend of my wedding -- a few friends and I paid a visit to a local book and ephemera auction. Today is the annual Pioneer Valley Book and Ephemera Fair in Northampton and, while I’m tempted to go just to browse, after buying antiquarian books at auction I don’t think I could stomach the retail prices -- especially at a fair, where prices tend to be inflated.

This week’s book was part of one of the two lots I picked up at that auction; indeed, it’s the reason I bid on the lot at all. As I’ve mentioned before, bidding on pre-set lots means one can end up with some things one doesn’t want (for that reason I’m starting to expand Tarquin's online presence to include a re-selling operation on Ebay -- going to try to free up some precious space on the shelves in Tarquin Tar’s Bookcase...). At this particular auction, part of the sale was “pick lots” -- meaning the individual bidders could rummage through around forty boxes of books and make up our own lots. One of the two lots I won was a pick lot that I assembled; but this second lot was pre-set. Fortunately, all of the books in it are fascinating and worth adding to my collection (though many are from broken sets). This week’s book is one of the more choice items from that pre-set lot.

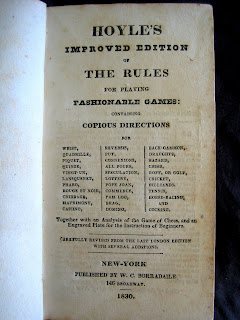

The book’s full title is Hoyle’s Improved Edition of The Rules for Playing Fashionable Games at Cards, Etc. It was published by W. C. Borradaile of 146 Broadway, New York, on June 2, 1830. Edmond Hoyle (1672-1769; the cheerful fellow to the right) was a lawyer who became a whist teacher and gaming aficionado; he collected for his own use and the use of his students the rules of various card games, board games, and sports games and in 1742, for his students, he published a booklet on the rules of whist. The first edition of his collected rules was published in London in 1750 and contained only whist, chess, draughts (checkers), and backgammon. In subsequent years, Hoyle published individual pamphlets for various other games; the posthumous 1775 London edition of Hoyle’s Games Improved, prepared by James Beaufort, was the first “full” collection of these pamphlets in one book.

These early editions are highly collectible because so few survive (only two copies of the first edition are still extant); though printed in large numbers, they were heavily used and thus fell apart over time. Many more English editions followed, and, in 1796, the first American edition appeared in Philadelphia (H. & P. Rice). Over the years, other authors and publishers have added to the collection, resulting today in a compendium of over 250 games. Though the rules of many of the games have changed over time, the term “according to Hoyle” or “Hoyle’s rules” is still used to mean “according to official rules”.

The contents of the 1830 New York edition, which have been “carefully revised from the last London edition with several editions” include “copious directions” for dozens of games -- many names of which may be somewhat quaint to a modern reader:

Whist; Reversis; Back-Gammon;

Quadrille; Put; Draughts;

Piquet; Connexions; Hazard;

Quinze; All Fours; Chess;

Vingt-Un; Speculation; Goff, or Golf;

Lansquenet; Lottery; Cricket;

Pharo; Pope Joan; Billiards;

Rouge et Noir; Commerce; Tennis;

Cribbage; Pam-Loo; Horse-Racing;

Matrimony; Brag; Cocking;

Cassino; Domino

The book is bound in worn full-sheep leather and has a calf-leather gilded-title label on the spine (the label is coming loose). The pagination runs [i-iv], comprising the frontispiece and an ornate half-title, followed by the contents starting with the full-title page, running [1]-288. The book ends with a blank flyleaf. There is no marginalia; it is in generally good condition, with some foxing (particularly on the more acidic illustrative plates) and folding of pages and some bumping and chipping of the binding, but no major damage. The pages measure 7cm x 13cm and are of a common machine-made stock. The book may be expressed collationally as 16o: [#2] [A12]-M12 [π]: $1&2[5]. The small sixteenmo format lends itself very well to the book’s most obvious use: being carried in one’s pocket for quick and easy reference while out playing cards with friends or at the club.

Each chapter generally begins with a brief summary of the nature of the game, followed by sections on the terms used in the game, the “laws”, and a description of the game being played. Some of the more complicated games, or games requiring boards, have detailed explanations, charts and diagrams, and illustrated plates. The longest chapter by far is that on Whist; in addition to Hoyle’s instructions, it includes “Mr. Paine’s Maxims for Whist” (123 suggestions and tips) and Mathews’s Directions (another approximately 120 rules from Thomas Matthew’s 1804 London edition of Advice to the Young Whist Player, included in this edition so that “the student may compare them with Hoyle’s and Payne’s [sic] maxims and directions, and follow such as appear most reasonable and practical”). Hoyle ends the section with a brief reflection on etiquette during play and the proper way to behave if you find your partner’s play disagreeable.

Many of the other chapters are brief -- only a page or two -- though some (such as chess and draughts) are quite extensive. My American readers will be amused to know that the rules for cricket only take up two and a half pages. Golf covers less than two pages.

In addition to these chapters, there is a special section in the chapter on chess that provides a move-by-move “analysis of the Game of Chess”; the title-page also promises “an engraved Plate for the Instruction of Beginners” in the game, but that folding-plate illustration has, sadly, been removed from my copy. The chapter on draughts also provides twenty move-by-move games to help novice players see how certain moves follow logically from other moves.

Besides simply presenting rules (and sometimes historical origins) for the games, Hoyle -- being a proper English gentleman -- can’t help from slipping in some passing mention of his personal opinions on some games and their variants. For “four-ball billiards”, for example, he reflects with a Tory sniff: "This is very properly styled the Revolution game, it being subject to as many different vicissitudes as that monster of changes is susceptible of" (270).

On pool, that clumsy billiards variant played by those provincial colonists, he begins simply, “The system of this game is very imperfect, and...inefficient” (271). On cock-fighting, Hoyle begins, “This game, if it may be so called, had its rise and adoption in the earliest times among the Barbarians” (284). More positive is Hoyle’s view of Backgammon: “The Game of Back-Gammon is allowed on all hands to be the most ingenious and elegant game next to chess” (161). Besides individual games, he also has particular opinions on styles of play; for example, in reflecting on how best to play chess, he notes that “bold attempts make the finest games” (211). There is an appealing suggestion, here, that winning or losing is sometimes secondary to the elegance of how one plays the game. As he puts it later, “[I]f, after all, you cannot penetrate so far as to win the game, nevertheless, by observing these rules, you may still be sure of having a well-disposed game” (214).

The book begins with a frontispiece engraving by “Tuthill” showing two men and two women seated around a table, thoughtfully engaged in a game of cards. The two men stroke their chins and smirk knowingly; one woman has her back to us (can’t see her cards, though), and the other woman has her arm draped across the back of her chair as if daring someone to call her bluff. The other illustrations are a backgammon board and a draughts board. As noted above, there was originally also a fold-out illustration of a chess board but it is missing from my copy (alas).

Given my recent state of espousal, I’m particularly intrigued by the game of Matrimony and Hoyle's authoritative description of the rules of the game: “The game of Matrimony is played...by any number of persons, from five to fourteen. The game consists of five chances” (116). Who knew?

Sunday, October 3, 2010

How to Get Rid of a Woman

This will be my last post as a bachelor! (Sort of...I haven’t really been a bachelor in six years -- but now it will be legal.) To commemorate this momentous occasion, this week’s post features a book from my collection that I will no longer need to read.

The full title of this flapper-era novel is How to Get Rid of a Woman: Being an Intimate Record of the Remarkable Love-Affairs of Wilton Olmstedd, Esq., Man of the World and Student of Life, Together with His Revealing Impressions of Women and His Amazing Discoveries Concerning the Sex. The book was written by New York-born writer and journalist Edward Anthony (1895-1971), who spent much of his later life in Gloucester, Massachusetts.

Anthony’s early career was spent as a journalist for several newspapers, including the New York Herald from 1920-23, and as a writer on the staff of some magazines (including the humor magazine Judge); in 1928, Anthony joined Hoover’s campaign for president, serving as his press director for the east coast. He is probably best known, however, as the co-writer of actor and game hunter Frank Buck’s first two books, Wild Cargo (1932) and Bring ’Em Back Alive (1930). Later, Anthony served as publisher for Woman’s Home Companion (1942-52) and Collier’s (1949-54), and he wrote an autobiography that was published in 1960.

How to Get Rid of a Woman was published in only one edition in 1928, by The Bobbs-Merrill Company of Indianapolis. It was machine-printed by the book manufacturing abd binding firm of Braunworth & Company, Inc. in Brooklyn, New York. No subsequent edition was published; the book is not terribly uncommon and is valued at around $25.

After an unpaginated flyleaf, the contents run [1]-[319], followed by a final blank fly at the back. At the start of each of the twenty-two chapters there is a black-and-white drawing by Mexican caricature artist George de Zayas (1898-1967), whose comically elongated figures gained fame as symbols of the sleek style of the Jazz Age and were to be found in the pages of publications such as Collier’s and Harper’s. Occasionally, a black silhouette illustration appears at the end of a chapter as well. The image on the title page shows Olmstedd, in a tux, standing haughtily over an audience of women who stare at him while he pontificates smarmily.

In the Foreword, Anthony provides a fictional account of how his book came to be. On the title page he is credited simply as the “editor” of the “Olmstedd’s” narrative, and in the Foreword he explains this further by inventing a story about meeting the character of Wilton Olmstedd; after an engaging discussion over dinner about “some of his remarkable experience with women”, Anthony proposes collaborating on a book with the lothario (much as Anthony had actually collaborated on Buck’s books around the same time). “Many a man has had a busy love-life,” Anthony tells Olmstedd, “Who besides you, however, has discovered how to dispose of a woman?”

The rather fully-written titles of the book’s chapters provide a complete plot summary of the episodic narrative (see photos below).

In short, our Don Juan of the Roaring ’20s moves rapidly and rather callously through a series of short-lived affairs, through which he develops a pseudo-philosophy on both how to get out of a relationship and the benefits of doing so. He concludes his “memoir” with ebullience at the termination of one particularly long-running liaison:

How wonderful it is to be free! How grateful I am for my lack of fetters! It is a “grand and glorious” feeling. Nothing gives me quite so complete a sense of well being. Nothing is a better guarantee of a calm and peaceful life.

Glancing through the book, and looking at the chapter titles especially, there is a distinct sense of mockery in how Olmstedd is portrayed. On the surface, he is carefree, cheerful, and self-satisfied; but the shadows of the book convey a darker, more satiric view of the character: he is hedonistic, shallow, misogynistic, condescending, perpetually unsatisfied, and oblivious. Indeed, from the very first self-lauding line of the book, one cannot help but loath Wilton Olmstedd, Esq.: “Why am I so popular with the ladies?”

The book is bound in yellow cloth with a Zayas portrait of Olmstedd’s head inside a heart on the cover. My copy has suffered some bad water damage to the cover; though the binding and hinges are intact (though loose), it is quite discolored along the bottom. As is usual with fiction, there is no marginalia, though one page is dog-eared and the rest have the usual wear, water-stains, and wrinkling of use (though no damage obscures the text). On the recto of the front flyleaf there are some pencil inscriptions in an imprecise cursive hand; they seem to be names (“l a gardiner” and “Raymond Maris”?). On the verso of the back flyleaf, there is some more evidence, however, about past use. Beside some pencil squiggles (mostly numbers) and the book’s title in blue pen, there is a library stamp and then a long column of check-out stamps. The library stamp reads:

Rental Library

Meekins, Packard & Wheat Book Shop

Conducted by

Doubleday, Doran Book Shops

Springfield, Mass.

Meekins, Packard, and Wheat was a monumental and highly successful department store located at 43 Hillman Street in the city of Springfield in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. As with most department stores of the time, the firm ran a paid rental library as part of the business; evidently they contracted publisher Doubleday & Doran to run the shop. According to the date stamps, How to Get Rid of a Woman was checked out twenty-two times between August 1 and December 15, 1928 (the registration for the copyright on the book is also dated August 1, 1928, so the copy at the rental library was brand new when it was checked out; Anthony renewed his copyright on September 2, 1955, shortly after his retirement from Collier’s, but not second edition was issued). Interestingly, the duration of time between some stamps is only one day, indicating that whoever was reading the book managed to get through it all overnight in some cases.

What happened after December 15, 1928 is a mystery; perhaps the book was returned and simply sat idle on the shelf, a relic of a happier time that few cared to think on following the chaos of 1929. Perhaps the store management decided that the title had gone stale by mid-December and pulled it from the shelves to make space for the new holiday stock (only one person checked it out in all of November, and only three in December). Or (more likely, I think) perhaps the person who was supposed to return the book on December 15 simply did not, and the book was effectively stolen from the Meekins, Packard, and Wheat rental library.

As with most library books -- whether in private, public, or rental libraries -- the dust-jacket was removed from my copy of How to Get Rid of a Woman before it was put out for circulation. However, two pieces of it were cut out and retained by being pasted inside the front cover and on the recto of the front flyleaf. The piece on the flyleaf is a colored Zayas illustration of Olmstedd looking rather sly as a group of gawking women’s heads poke in from the edges. The piece inside the front cover offers up some unique (and completely fabricated) “testimonials” about the book.

As a final note, Tarquin Tar will be taking a break next weekend as I’ll be off to celebrate my nuptials with a brief vacation in Maine. See you in two weeks and -- as I will be ignoring the advice of Mr. Olmstedd, Esq. -- at that point I’ll be a married man!