"Let your bookcases and your shelves be your gardens and your pleasure-grounds. Pluck the fruit that grows therein, gather the roses, the spices, and the myrrh. If your soul be satiate and weary, change from garden to garden, from furrow to furrow, from sight to sight. Then will your desire renew itself and your soul be satisfied with delight." - Judah Ibn Tibbon

Sunday, November 29, 2009

Vacation

Sunday, November 15, 2009

A Family of Pioneering Educators and their Copy of the First American Edition of "Hudibras"

This week’s book offered me the intriguing opportunity to try to track down the physical movement of a copy as it traveled between owners. The book is titled Hudibras, in Three Parts: Written in the Time of the Late Wars...with Annotations and a Complete Index, an epic verse satire written by the royalist Anglican Samuel Butler during England’s civil war (1642-1660). The tale follows the misadventures of the ridiculously over-confident and under-skilled knight errant and his long-suffering squire. Like Don Quixote, Sir Hudibras encounters a series of mundane and everyday people and events and mistakes them for true chivalric conventions. Unlike Don Quixote, his screw ups and his inability to distinguish truth from fiction is not because of an overbearing sense of romanticized idealism but simply because he is an idiot.

The epic was first published in London in three parts in 1663, 1664, and 1678 (Charles II had been restored to the throne in 1660, making mockery of the Parliamentarians, including Cromwell, much more publicly acceptable by the time Butler published his satire). In addition to ridiculing the writer’s political foes and religious opponents (Puritans and Presbyterians), the work also pokes fun at ludicrously hyperbolic and stilted styles of poetry from the time.

My copy was printed and published in 1806 by the firm of Wright, Goodenow, and Stockwell, in Troy, New York, and was sold by the firm at their Rensselaer Book-Store (not associated with Troy’s Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, which did not open until 1824). This makes my copy, as the title page claims in elaborate font, the “First American Edition”. The second American edition did not come out until 1812 (published F. Lucas Junior and P. H. Nicklin, of Baltimore). The work was very popular in England and Scotland, however, and it seems that Wright, Goodenow, and Stockwell, for their copy, simply reprinted one of the UK editions.

I have not been able to determine which one precisely was used, but they did reuse the prefatory material (a note “To the Reader” and “The Author’s Life”) and annotations originally provided by Zachary Grey in his edition of 1774 (which included illustrative plates by none other than William Hogarth). The publishers of my copy were evidently unaware that some of Grey’s claims had been modified more recently in John Bell’s Poets of Great Britain (published originally in 1777 and republished by the British Library in 1797).

The most substantive variation to the 1806 edition’s form was the decision to move all of Grey’s annotation from the back of the book to the foot of the page of text itself -- no doubt a concession to (American) readers for whom much of the epic’s dense and historically specific allusions and humor required a heightened degree of explanation. The editors also included some additional glossarial notes at the foot of pages and, in a few places, an explanation of a typographic error in their copy-text (see the final photo in this post).

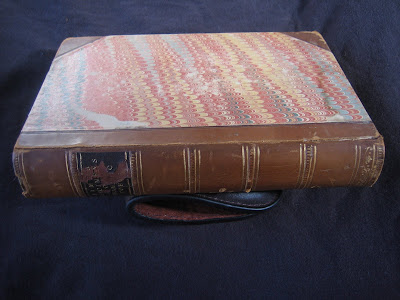

The book is bound in soft brown sheep leather, with some faded decorative tooling and a dark leather title label on the spine (see the photo at the start of this post). In binding the book, the printer did an excellent job: aside from some splitting to the front hinge, the spine is very tight and strong. The pages measure 10cm x 17cm and are of a sturdy though not particularly expensive paper stock with no evident watermark. The pagination runs [i]-xi from the title page through the end of the “Author’s Life” and [1]-286 for the content; a 13-page unpaginated “Index” of important concepts and events written in comically implicit language, keyed to page and line number, concludes the book.

At the front there is a flyleaf, marbled on the recto (as is the pastedown) and blank on the verso, followed by two blanks; at the end there is a blank followed by a fly similarly marbled and conjugate to the final pastedown as the first. There are no catchwords and no variants to the running-titles. Signatures are alphabetic and appear on the first and third leaf of each gathering (the first leaf is signed with the sheet letter; with the exception of the final gathering, in which it is not signed, the third leaf of each is signed with the sheet letter followed by “2”). It may be collated as 12o: [#3] [A6]-Aa6 [π]. The type is a small pica throughout and is often so firmly impressed into the page that the bite has left a rippling, tangible texture to the paper (see the image below) -- a rich tactile reminder of the physical process by which the book was created. With the exception of a few pages, the type was fully inked.

As I mentioned at the start of this post, this copy of Hudibras afforded me the opportunity to sleuth out how an early nineteenth-century book moved around the young United States. There is little evidence of early readers within the content of the book itself, aside from an erased pencil note on the first page, an erased pencil doodle later in the preface, and some page corners that were clearly once dog-eared as place-holders. In the blanks, however, there is some more useful information.

My book is ex libris, bearing an erased pencil record of its (Library of Congress) catalog number. Inside the back cover there is a computer-printed label reading “A22901 059017” (accession number, perhaps?) and a label with the LoC number PR 3338 A7 1806. Typed in red on the label is the word “Vault”, suggesting the library kept the book in a special restricted-access area for rare books. Inside the front cover there is a bookplate indicating the library from which the book came: Springfield College, founded in 1885, in the city of Springfield, MA. According to the bookplate, it was given to the college library as part of the “Carolyn Doggett Memorial Collection”. The bookplate indicates that the college’s name at the time it was given was legally “International Y.M.C.A. College”, but the seal shows the name “Springfield College”, meaning the book must have been given (or the bookplate put in) after 1939 (when “Springfield College” was adopted as the institution’s public moniker) and before 1954 (when “International Y.M.C.A. College” was formally removed as the corporate name). It is only by finally coming to Springfield College and its history that I can begin to piece together the narrative of this book’s travels.

From 1896 to 1936, the President of Springfield College was Laurence L. Doggett. Laurence’s wife was his college sweetheart, Carolyn Doggett of Providence, Rhode Island; from 1898 to 1928, Carolyn provided what her husband called the “cultural background” he felt the College’s students needed in their comprehensive education; she taught classical and modern literature, art, and music for the duration of her husband’s tenure as President.

In his 1943 Man and a School: Pioneering in Higher Education at Springfield College (dedicated to his late wife, whom he terms his “Comrade in Pioneering”), Laurence explains a little about his family history -- and in the process helps illuminate the history of my copy of Hudibras. The Doggett family traces its roots in America back to Thomas Doggett, who arrived in Marshfield, Massachusetts in 1637. The family was always involved in educational “pioneering” -- they were involved with administration at Brown University and in 1796, Laurence’s great-grandfather Simeon founded Bristol Academy and was “the pioneer of liberal education in the old colony.” (He was also the subject of a brief biographical sketch, written in 1852). Laurence’s grandfather, Samuel Wales Doggett, started a school for women in South Carolina. When Samuel died, his widow (Laurence’s grandmother, Harriet Doggett) moved to Manchester, Iowa, where she lived until her death in 1892. Her son was Simeon Locke Doggett, who, after obtaining his law degree in Worcester, Massachusetts, returned to Manchester in 1856.

A blind impression stamp on one of the blanks at the start of the book reads “S. L. Doggett / Notary Seal / Iowa.”, and penciled on the recto of the blank before that is the large signature of “S. L. Doggett”. More faint is a penciled inscription in a different hand, running vertically on the verso of the flyleaf and facing the signed blank: “Samuel W. Dogg[ ]”. Beneath that is a second illegible inscription in the same hand. According to the 1878 History of Delaware County, Iowa, Simeon was first hired as a county clerk in 1860 and then served variously as clerk or justice of the peace (or both) through at least 1877 (when the record ends). In 1865 he drafted a petition to the state asking that the village of Manchester and the surrounding villages be incorporated into a town; the petition was approved by the county and then the state in 1866. In 1870, 1871, 1872, and 1876 he was elected mayor of the town. He also served as chair of the school board for many years.

His interest in Butler’s Hudibras, and in literature in general, is attested to by his involvement with the Manchester Select High School, which he and his wife, Mary, founded in 1858. There he was head of the classical department and taught the classes in literature (in his own memoir, his son recalls Simeon reading works “aloud with dramatic feeling”, including The Vicar of Wakefield, The Arabian Nights, and the works of Scott and Dickens, as well as, of course, the Bible). His younger sister, Gertrude was the school’s assistant and later “Preceptress” for a year; she is described as “a lady of rare native grace and of brilliant accomplishment”. Gertrude went on to teach literature and elocution, eventually becoming a Shakespearean actor in Chicago and mother of the novelists Charles Norris and Frank Norris.

In 1860, Simeon gave an address to the county’s first Teachers’ Institute, and while no record of what he said survives, he is described as “one of the pioneer teachers of the county”. The county marriage records show that he was still active as a notary there through at least October 1886; in June 1929, Mary provided music for the funeral of Susannah Coon, in Henderson, Iowa, at which Simeon served as pallbearer.

His son, Laurence (shown to the left, towards the end of his time at Springfield College), ended up attending Oberlin for theology, where he became active in the Young Men’s Christian Association. This eventually led to some time at the University of Berlin and in Leipzig (Carolyn also studied at both places with her husband), and finally his position as President of Springfield College. Presumably Laurence inherited his father’s books (including my copy of Hudibras). Because the book was given as part of a “Memorial” collection, he probably donated it to the College’s Library after 1943 (the date of Laurence’s memoir and its dedication to the memory of his late wife) but before 1953 (the last year the name “International Y.M.C.A. College” would appear on a bookplate for the College library). At some point between that date and 2007 it was deaccessioned from the collection for some reason, and it made its way up to Antiques at Deerfield in historic Deerfield, MA, where it was purchased to be added to Tarquin Tar’s Bookcase.

The book has gone from upstate New York to Massachusetts, South Carolina, Iowa, possibly Ohio and Germany, and then back to Springfield, Deerfield, and finally (for now) Leverett, Massachusetts. To say nothing of many possibly unrecorded trips between each temporary stop. When we look at our own books in the relatively immediate context of our own lives, they seem to be perpetually stationary -- sitting on their shelves, silently gathering dust. But when we look at them in the trajectory of history, our books are always moving -- far more, even, than any single one of their owners.

Sunday, November 8, 2009

Charles Lamb on the Greatest Hits of the Renaissance Stage

My brain this week is stuck in preparatory mode for my doctoral qualifying exams on Friday (yes, that’s right...Friday the 13th) and so this week’s book is related to my exam on the history of the book.

In my exam reading, one particular issue that has caught my attention within the field of editorial studies is the practice of anthologized editions -- how are they assembled and why, what is included and what is excluded, in what order is the material presented, and how are they used? One particular class of anthologized works is the “greatest hits” collection; usually an arbitrary selection of some material that the editor, in his or her subjective judgment, thinks is representative of the period in question.

This week’s book is a late American edition of English poet, critic, and essayist Charles Lamb’s classic of the anthologized Renaissance drama genre: Specimens of English Dramatic Poets Who Lived About the Time of Shakspeare [sic], With Notes. Lamb’s eclectic collection was first published by Longman, Hurst, Rees, and Orme of London in 1808. My copy was published by Willis P. Hazard of 190 Chestnut Street in Philadelphia, PA, in 1856. The title page bills the book as a “New Edition” and presents the contents of the original two-volume set in a single volume. It was printed by Philadelphia book and job printer Henry B. Ashmead, whose substantial, five-story shop was to be found on George Street just above Eleventh Street (that is, at today’s 1104 Sansom Street).

Lamb's book was one of the more popular of several nineteenth-century excursions into the drama of the sixteenth and seventeenth century, going through subsequent editions in London, Philadelphia, and New York in 1808, 1845, 1849, 1854, 1856, 1859, and throughout the twentieth century. As with most of the other anthologies of Renaissance drama from this time, the material selected is almost always couched in explanatory material demonstrating the superiority of Shakespeare -- though Lamb does claim that part of his objective was “[t]o show what we have slighted, while beyond all proportion we have cried up one or two favorite names” (a flaw that modern scholarship has still done relatively little to rectify).

The preface that Lamb provided to the first edition -- and that remained largely unchanged in all of the subsequent editions -- makes his intentions clear; it also indicates how unapologetically intrusive and judgmental the editor was in picking out parts of plays to present and modifying them to suite his tastes (and those, he presumed, of his readers) -- see the third paragraph of the preface in particular. As he puts it, his “leading design” was always “to illustrate what may be called the moral sense of our ancestors”, and he had no qualms about tidying up the texts (though, to be fair, he never goes quite as far as some infamous meddlers did).

The range of material Lamb has selected for inclusion is quite impressive: Thomas Sackville and Thomas Norton, Thomas Kyd, George Peele, Christopher Marlowe, Robert Tailor, Joseph Cooke, Thomas Dekker, John Webster, Anthony Brewer, John Marston, George Chapman, Thomas Heywood, Richard Brome, Thomas Middleton, William Rowley, John Ford, Cyril Tourneur, Samuel Daniel, Fulke Greville, Ben Jonson, Francis Beaumont, John Fletcher, Philip Massinger, James Shirley, Nathan Field, and the ever ubiquitous “Anonymous”. These writers represent a broad range of dramatic traditions (professional, academic, literary), a relatively wide period of time, and many different genres and styles.

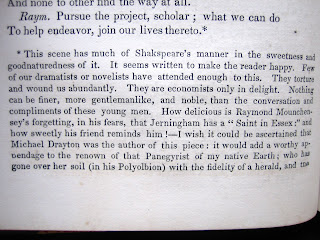

Lamb’s style of presenting the works of these plays consists of selecting choice passages or scenes from various plays and presenting these passages with explanatory headers (often summarizing the passage’s “theme”), annotation including glossarial and critical footnotes, and added stage directions and explanations of action that has been skipped over. The overall effect is rather disjointed and the textual authority of the passages is highly corrupt, though as far as providing access to relatively obscure playwrights and their important works, Lamb did his contemporaries and many later readers a great service.

The pages measure 12cm x 18cm. Ashmead evidently carried out the printing by separating the two volumes into two separate jobs. The pagination of the first volume runs [i]-[xii] [1]-220 and the pagination of the second runs [v]-vi [1]-230; the lack of two leaves at the start of the second volume (that is, pages i-vi) suggests that a dividing, internal half-title and “flyleaf” was meant to be inserted but was for some removed before binding.

The book is printed in octavo, with numeric gathering signatures; on each signed page, there is also an indication of which volume the gathering belongs to (again, suggesting separate but likely simultaneous printing in Ashmead’s shop). The use of machine press seems likely because of the date and the scale of Ashmead’s operation, but the mechanization of the craft has unfortunately resulted in some problems with inking: the type on many pages is often under-inked, blurred, or scarred; indeed, sometimes one page in an opening will be visibly fainter than the facing page -- suggesting the outer and inner formes were being inked separately and not in synchronization.

The binding is a firm hardcover with marbled boards, a leather spine with gilt title, and leather corners. The spine is cracking slightly, especially along the front hinge, and the spine has some damage, but overall the condition is quite good. The only evidence of earlier readers consists of some faint pencil marks next to some of Lamb’s notes, two sentences in his preface, and the title of Ford’s The Broken Heart in the table of extracts in volume two. These may have been made by the same owner who pasted the “Underhill” family bookplate inside the front cover. The bookplate presents the family crest over a Latin phrase that I welcome help with: “Tibimet ipsi fidem praestato”.

Lamb’s book uses the ahistorical “greatest hits” methodology in anthologizing Renaissance drama, though it broadens the field considerably by drawing in a number of works that even most scholars today wouldn't bother reading. Lamb takes the practice to an even higher level of selective control by removing passages from their context and presenting only “extracts”.

This was something that certainly appealed to Lamb’s own predilections as a poet (rather than a scholar, historian, or theatre practitioner) -- he desperately wanted to believe in the discrete, detachable, and discernible nature of poetic genius and its products. Indeed, the practice did not die in the nineteenth century; at least one prominent twentieth-century poet took it up himself to adjudicate on the “essential” poetry of Shakespeare, removing the passages rather brutally from their appropriate dramatic context in so doing.

Sunday, November 1, 2009

Historic Salem For the Day After Hysteric Salem

This week’s book has personal meaning to me, as a keepsake from my home town, but it is otherwise not incredibly rare or valuable. The title is Historic Salem in Four Seasons and the contents offer a sepia-toned journey along the streets of Salem in the form of a photo essay (or, as the title page puts it, “A Camera Impression”) by noted Marblehead artist-author Samuel Chamberlain (1895-1975) (the Peabody Essex Museum has some examples of his work in their Essex Image Vault). The book was part of the American Landmarks Series and was published by Hastings House of New York in 1938. The type (garamond font) was set by hand by craft printer Elaine Rushmore at the Golden Hind Press (1927-1963) in Madison, New Jersey.

The firm of Hastings House was founded in the mid-1930s by Walter Frese specifically to serve as an outlet for Chamberlain’s work; most of the firm’s four dozen books featured New England (and especially Salem) colonial architecture. A second firm -- Stanley F. Baker of Madison, NJ -- published the second issue of the edition. Interestingly, when Baker published his version, he simply stamped an ornate vine-and-leaf pattern over Hastings’s imprint on the bottom of the title page and then stamped his own name and address beneath that (see lower photo below). This is what is known as a "cancel imprint" and was sometimes done in the form of stamps, but also as stickers or tipped-in slips. It is surely significant that both the Golden Hind Press and Baker were located in Madison; indeed, a review of an admittedly incomplete bibliography of the Press’s output reveals the name of Karle Baker in 1927 (and several Rushmores as well). No subsequent editions were published.

The binding is paper-backed orange boards, lettered in white, with a white spine (it originally had a dust-jacket that mine now lacks). The pages measure 15cm x 18.5cm. The gatherings are rather irregular; the pagination runs from the title-page to the last page [1]-[74]. The front flyleaf is conjugate with the front pastedown; the pastedown and recto of the fly offer a panoramic shot of Pioneer Village in the snow. Likewise, the verso of the final leaf and the rear pastedown provide a panorama of historic Chestnut Street in the spring.

In the foreword, Chamberlain sets out the objective of his book (beginning, it seems, with a dig at Eliot’s Five Foot Shelf?):

No five foot bookshelf could hold the volumes which have been written about Salem. So many of them have done justice to their illustrious subject that a new book may seem almost presumptuous without a word of explanation. It is hoped that this pictorial volume on Salem will be justified for two reasons.

First, it is a contemporary record of historic Salem. Time passes quickly, even in Salem, and it causes startling and sometimes irreparable changes. The dated document has a certain value, be it an old engraving, a panoramic painting, a bird’s-eye sketch by a schoolboy or an old photograph. Secondly, though Salem has been treated handsomely by the printed word, good photographic records are rare indeed. Yet it is an American landmark of extraordinary significance, and frequently, great beauty. The observant visitor to Salem carries away a vivid mental picture which can be preserved, or at least refreshed, by good pictures. If this small book can serve this one purpose, without any pretense of being a guide or a history, it will be privileged indeed.

Chamberlain’s comments -- ironic, if not whimsical, to a modern reader -- go on to suggest that one must “wander” the city to find the best sites, and he settles on Essex Street, Federal Street, and Chestnut Street as the finest of the lot (he is interested in architecture, after all). He also avers that Salem’s “most beautiful moments are in winter, when few visitors see it” -- a sentiment the still rings true today and that has special sentiment as I write this on November 1st, the first day of Salem’s lengthy “down season”.

The contents of the book span more than just the three streets noted above, however, and span throughout the seasons. They include a mix of interior and exterior shots of places such as: the Custom House, the “Market House” (Old Town Hall), the “City Almshouse” (also in the photo is the old “City Insane Asylum”) on Salem Neck, Charter Street, Pioneers’ Village, Gallow’s Hill, the “Witch House” (Jonathan Corwin House), the Pickering House, the House of the Seven Gables and properties along with other Hawthorne-related sites, Derby Wharf (in the state of disrepair that characterized Salem’s maritime fortunes after the 1890s), the Derby House, Charter Street Burial Ground, the Essex Institute and its properties, the Peabody Museum’s East India Marine Hall, the Arbella replica and modern yachts, St. Peter’s Church, Washington Square, many houses around the Common, the Ropes House and carriage house, “Salem Doorways”, a number of houses from the McIntyre District, Hamilton Hall, and, of course, Chestnut Street. There is also a page of three gate-posts, with the accompanying bold claim that “It is perfectly safe to make the statement that Salem’s gate-posts and fences are the finest in the country” (Salem has a long tradition of building exquisite barriers between neighbors). As with so many other books offering historical photographs of places still in existence, much of the pleasure to be had in this volume lies in comparing and contrasting what was with what now is.

There are no owner’s marks or marginalia in my copy, but on the recto of the flyleaf there is a small sticker from a seller: “Old Salem Book Shop”, located at 319 Essex Street in downtown Salem (see above). I can’t find much information online about the shop. Its location is on the edge of the McIntyre District, across the street from the First Church -- not a spot typically thought of as commercial. The store was owned and operated for twenty years by Beverly resident Maxine O’Hara (1928-2008), though I have been unable to determine when specifically she was there and whether she founded it or it was in existence before her. As always, I invite my readers to help supply me with any more information if they happen to have it!