"Let your bookcases and your shelves be your gardens and your pleasure-grounds. Pluck the fruit that grows therein, gather the roses, the spices, and the myrrh. If your soul be satiate and weary, change from garden to garden, from furrow to furrow, from sight to sight. Then will your desire renew itself and your soul be satisfied with delight." - Judah Ibn Tibbon

Sunday, December 27, 2009

Holiday Hiatus

Sunday, December 20, 2009

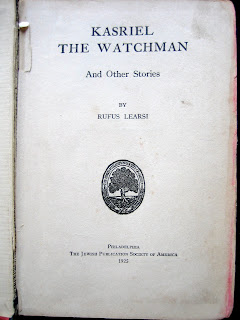

A 1925 Collection of Jewish Stories for the End of Hanukkah

Yesterday marked the end of Hanukkah this year and so this week’s book was chosen as a small nod to my half-Jewish heritage. The title is Kasriel the Watchman and Other Stories, by Jewish American scholar, historian, short story writer, and playwright Rufus Learsi. It was published by the Jewish Publication Society of America in Philadelphia in 1925 and printed by H Wolff. There was evidently a reliable demand for the book as reprints of the first edition followed from the Society in 1929, 1936, and 1948. My copy is of the first.

Tracking down biographical information on Learsi has been frustratingly difficult. The nearest I can come to an understanding of the man is from looking at the evidence of his other publications; judging from when he published I would guess his life range was approximately 1890-1965. His earliest work was a biography of one of the nineteenth century founders of the Zionist movement, Theodor Herzl, published by the Judean Press of New York in 1916. In 1917 he published Brothers (Mizpah Publication Company, New York) and in 1919 Zionism: Its Theory, Origins, and Achievements (Zionist Organization of America, New York). This work lead to Learsi’s involvement with more current political issues and in 1920 he wrote a book for the Committee on Protest Against the Massacre of Jews in Ukrainia and Other Lands, of the American Jewish Congress, titled The massacres and other atrocities committed against the Jews in southern Russia: a record including official reports, sworn statements, and other documentary proof. This was followed by a political text on the Zionist movement (His Children, published by The Jewish Welfare Board in New York in 1925), the same year that Kasriel the Watchman and Other Stories appeared.

His prolific work over the ensuing four decades appeared in a wide range of media, including newspaper articles and editorials, magazine articles, educational literature, stories, compendiums of Jewish humor, anecdotes, tales, and Hassidic ballads, nonfiction books and biographies from Jewish history (including, in 1949 -- one year after the founding of the modern state of Israel -- Israel: as History of the Jewish People), accounts of Jewish military history (these appeared, not surprisingly, in the late 1930s and early 1940s), many plays for both adults and children, and even one musical score (“Hail the Maccabees!” in the 1930s). Learsi is perhaps best known, however, for two publications toward the end of his career, both major studies of the Zionist movement in America and abroad: Fulfillment: the epic story of Zionism (Cleveland: World Publishing Company, 1951) and The Jews in America, a history (New York: World Publishing Company, 1954). Given the nature of events on the world stage in the decade following the founding of the modern state of Israel in 1948, the publication of these two books was greeted with a heightened degree of scrutiny in the press. Many reviewers took Learsi to task for his unapologetically partisan slant in his histories. A good example of this may be seen in a review of Fulfillment written by fellow Zionist Robert Weltsch in 1952:

Mr. Learsi's book is well written, carefully composed, and it sums up a wide range of relevant facts, moving with intelligence and skill over a subject of immense complexity; its language is mostly moderate and restrained, and the general reader can get from it a good picture of the historical and spiritual forces which created the mystique of Zionism and the modern Zionist movement.

But, like most histories of Zionism, this book is mainly a piece of propaganda, and this harms its value as a historical work. Mr. Learsi tends to accept uncritically, sometimes even naively, the official Zionist version of history; he sees all opposition as expressing a sinister malevolence, and thus he misses the essential drama of the story, which was—and remains—most often a story, not of right against wrong, but of opposed rights.

Information on the publisher of Kasriel is much easier to come by, particularly because the organization -- the Jewish Publication Society -- still exists. Founded in 1888, the nonprofit JPS was originally dedicated to providing second-generation Jewish Americans with English-language books about their heritage and their history. It has since expanded to include a larger audience and a broader range of books in different genres and on different topics. Most famously, JPS publishes a text of the Tanakh that is accepted as standard by most scholars, synagogues, rabbinical schools, and Christian seminaries.

My copy of Kasriel the Watchman and Other Stories is hardcover, its boards decorated with red cloth bearing repeated diamond-shaped pictures (an old, bearded man in a hat, alternating with a cityscape with a star or sun overhead). There are inconsistencies between each image on the decorated cloth, revealing that they were each individually drawn rather than stamped. The spine is black cloth; some dealers listing this book claim that titling is visible (usually faded) on the spine, but mine has no trace. The pages measure 12.5cm x 18.75cm and are of a heavy but not particularly expensive stock. It is in octavo format (some dealers list it erroneously as duodecimo) and the pagination runs [1]-311. The preliminaries (title page and copyright; blank conjugate with frontispiece; dedication and thanks; contents] are unnumbered, as is the final blank flyleaf conjugate with the rear pastedown.

The book is in rough condition: the spine is quite tattered and the corners of the boards are bumped; the first three leaves of the preliminaries are loose; some page corners are dog-eared; slight water-staining occurs throughout (never interfering with text, though); in some openings the spine is splitting slightly; and, most oddly, there are some ancient, dried crumbs of bread scattered on the first page of the story “The Beggar’s Feast”. The book has clearly been well-read over the years. Despite this, however, there is little evidence of owners’ writing in the book (perhaps not surprising; there seems little reason for a reader to mark up or annotate in any meaningful way a collection of stories such as this -- as opposed, for example, to books such as textbooks, scholarly works, nonfiction, religious books, etc.).

The only previous owner’s marking occurs on the recto of the blank leaf between the title page/copyright and the frontispiece plate; the name “Morton Margolis” is penned in faint blue ink and blocky letters in the upper right corner, and beside it there is an excellently drawn portrait of an old bearded man in a flat (Russian?) hat, inked in watery green ink (perhaps watercolor paint?). I have no verifiable lead on who this man might have been, though there was a late Morton Margolis who was a professor of humanities at Boston University and also a practicing artist. According to his November 1990 obituary in the Boston Globe, Margolis specialized in the connections between music, art, and literature and was known for “enliven[ing his] lectures by playing...on the piano.” If this man is the same Margolis who owned my copy of Kasriel, his delicately detailed painting on the blank leaf certainly does offer a connection between art and literature -- in a very unique and personalized way.

Evidently Learsi obtained the material for his collection of stories from tales he had heard as a child (the dedication reads: “This medley of childhood memories I dedicate to my mother.”), and so the target reader was likely young Jewish boys of the post-World War I generation (though the stories themselves would hearken back to a pre-World War I Jewish community in America -- the time and place when Learsi was a child). There is also a special publisher’s note following the dedication that I have been unable to decipher: “The Jewish Publication Society of America is indebted to NATHAN H. SHRIFT, of New York, for aiding in the publication of this volume.” Who “Nathan H. Shrift” was I cannot tell; my suspicion is that, because the JPS was a nonprofit organization, Mr. Shrift was a benefactor who fronted the capital for the publication, but I have no evidence of this.

Included in the book are five illustrative plates inserted into gatherings on semi-glossy stock (including the frontispiece); at least one dealer online lists another copy of this edition with seven plates, which seems to suggest that two have fallen out of my copy at some point (the perils of illustrative plates that are not integral to a book’s gatherings). The artwork is fairly standard, representational black-and-white drawings that depict moments from the stories into which they are bound. These pictures are signed “R. Leaf”; I assume that this is Reuben Leaf, a prolific New York artist who taught an Arts and Crafts Group at the famed 92nd Street Y in the 1930s and whose illustrations accompanied many Jewish American books from the 1920s through the 1950s. Leaf also published his own art books through his studio imprint (most famously, his Hebrew Alphabets: 400 B.C.E. to Our Days in 1950 -- a work of beautiful graphic art but that received some scathing notices for including a large amount of inaccurate scholarship on its subject).

Learsi has organized his book into five groups of stories; each of the first four groups centers on one or two recurring main characters (“Kasriel the Watchman”, “Perl the Peanut Woman”, “Benjy and Reuby”, and “Feivel the Fiddler”) and the final group consists of varied “Phantasies”. The structure is broken up slightly by the occasional inclusion into these groups of unrelated miracles and legends from Jewish lore. Overall, the collection includes thirty-one stories. The final story, dedicated to someone named “David Emmanuel” (possibly a euphemism for the Jewish people?), is perhaps the most overtly political Zionist tale in the book.

Titled “The Severed Menorah: A Glimpse of the Great Tomorrow”, it tells of two Polish brothers (named, of course, David and Emmanuel) who go off to Russia to become scholars of Hebrew law. Their mother insists that they take the family menorah with them and pawn it for money to live on, but they cannot bring themselves to sell such a sacred object, though they take it with them for their mother’s sake.

Soon after, a great tempest of anti-Semitism sweeps through Europe and in the violence the two brothers are separated -- each taking with them a separate piece of the menorah (one the base and the other the branches). When the fighting finally comes to an end, the surviving Jews from across the globe make their way to the “Ancient Land” and to build a home for themselves. Many years go by until, one day, an elderly Jew from America goes to visit this new land. He eventually finds himself in a synagogue where an old rabbi is debating the law with his fellows; the tourist discovers to his surprise that their menorah consists only of branches inserted into a wooden base for support. From his bag, the man withdraws the missing base of the old menorah and so the two brothers -- like the menorah and like the Jewish people -- are finally united once more. An appropriate tale, I felt, at the end of this Hanukkah holiday. Tzeth'a Leshalom VeShuvh'a Leshalom.

Sunday, December 13, 2009

A Book from the Days When Titles Were Essentially Abstracts

This week’s book is a slightly worn copy of a mid-nineteenth century treatise on educating and raising a child. The wonderfully specific title, in full, is: On the Importance of an Early Correct Education of Children: Embracing the Mutual Obligation and Duties of Parent and Child; Also the Qualifications and Discipline of Teachers, With their Emolument, and a Plan Suggested Whereby All Our Common Schools Can Advantageously Be Made Free; The Whole Interspersed with Several Amusing, Chaste Anecdotes Growing Out of the Domestic and Scholastic Circle. To Which is Subjoined by way of an Appendix, the Declaration of Independence by the Thirteen North American Colonies, 4th July, 1776. The Constitution of the United States, with that of the States of New Jersey and New York, as Lately Adopted.

Written by Dr. William Euen, the book was also published for him privately by an unnamed New York firm in only one edition, two issues, in 1848. My copy is of the second issue (the first paginated to only 136, presumably because it lacked the New Jersey constitution, which runs pp. 137-152). It retailed, according to the title page, for sixty-nine cents (about $18.83 in today’s money). Its valuation to collectors today seems highly erratic: the second issue seems to be worth around $30 (the first apparently around $45), but at least one dealer is selling the second issue for a ridiculously inflated price around $340.

Dr. Euen was a resident of the town of Shawangunk in Ulster County, New York. His book is exactly what the title explains, using a fair amount of appeals to patriotism, civic planning, the Bible, and nineteenth-century pedagogical theory (including on the purchase of books, the use of writing paper, and the importance of using a goose quill and not resorting to those sinful "steel pens") to make its case.

Tracking down information about the man has been a bit difficult, but it seems that he was the same William Euen who had previously published A Short Exposé on Quackery (Philadelphia, 1840). Prior to that he was apparently residing in Newton, New Jersey (hence the inclusion of both the NY and NJ constitutions in his book) where, in February 1829, he renovated his home at 29 Liberty Street and converted it into the Euen School for Girls. It is possible that our author is the same man who ended up as the editor/co-publisher of the Weekly Prison City Item of Waupun, Wisconsin from 1860-June 1861 (the writing style of the two Euen’s is similar, though the topics they write on are rather different).

The book is bound in the publisher’s brown cloth with decorative blind tooling and gilt title on the cover. The pages measure 11.5cm x 18.5cm; pagination runs [i]-iv from the title page through the preface, [1]-152 for the contents of the book. The collation is rather peculiar; signatures are numeric and include an added asterisk to indicate a signature internal to a gathering (internal signatures are not used in the appendix gatherings). The format is another octavo in twelves (with the exception of the appendices, which were apparently printed separately in standard octavo format) and the formula may be expressed as 8o: [#2] [112]-412 58-88 [π]: $1, 5. In some places the printing was clearly a rushed job: type slips (for example, the “6” in the page number “86” is almost a full line lower than the “8”) and some of the ink has smeared or not been fulling applied to the type.

The condition is average: the last page is torn in half but still attached to the binding, the cover has some bumps and chipping, and there is some foxing and other paper stain damage (on which more below) throughout. The only owner’s marks are an apparently purposeful pencil mark next to a passage about the necessity of having a globe in the classroom and an owner’s pencil inscription inside the front cover on the pastedown: “H D Ryell, / Book”.

I chose this book for this week because the combination of child-rearing advice and New Jersey seemed an important coincidence for my family this month. But while I was leafing through it I came across another interesting feature. At first I thought I was looking at some severe staining caused by a liquid spill or moisture of some kind: mirror-image marks in the gutter of many openings, not unlike a Rorschach Test.

Eventually, however, I came across the dried, brown remains of a very old flower, pressed between two pages and, in another place, an explosion of dried, brilliantly red pollen; apparently some early owner (H. D. Ryell, perhaps?) decided that the most functional use for Euen’s treatise was as a tool for the highly popular nineteenth-century art of flower pressing. It would be interesting -- though beyond my capacity -- to try to identify the specific flowers that had been pressed in the book by researching their silhouettes. I began to reflect on the many different non-reading uses of books and came across this fantastic page with a range of highly artistic (and sometimes functional) alternative uses for books.

Try doing any of those -- or pressing flowers -- with a “Kindle”.

Sunday, December 6, 2009

A Salmagundi of English Anecdotes

The title is A Book for a Rainy Day: Or, Recollections of the Events of the Last Sixty-Six Years by John Thomas Smith (1766-1833; shown here). The first edition, published by Richard Bentley of New Burlington Street in London, appeared in 1845 and was quickly followed by a second edition in the same year; ironically, the first edition is far more common than the limited second edition. This copy is of the second edition. The printer for both was Schulze & Company of 13 Poland Street in London. Bentley and Schulze are perhaps best known for being the publisher-printer team behind the first book publication of Dickens’s Oliver Twist. Subsequent editions followed in 1861, 1900, and 1905 (edited by Wilfred Whitten). In 1846, the book was adapted into Charles Mackay’s two-volume An Antiquarian Ramble in the Streets of London, with Anecdotes of Their More Celebrated Residents.

Smith -- a character on the London social scene for much of the late eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century -- had been since 1816 the “keeper” of the British Museum’s prints and drawings collection, was an accomplished artist (mostly of portraits) and the author of several other works, most notably a study of London street life and crime titled Vagabondia and a biography of the sculptor Nollekens and His Times -- a book that was, according to the Cambridge History of English and American Literature, Vol. 14, “unmatched for malicious candour and vivid detail”.

As for his Book for a Rainy Day, the Cambridge History describes it as “one of the most entertaining and most trustworthy memorials of [Smith’s] period. Published twelve years after his death, it forms a valuable corrective to the flashy fictions of Egan and his life.” The book takes the form of a highly detailed, largely autobiographical diary of London society over the course of Smith’s life, ranging from theatre news to political scandal to high society gossip to literary anecdotes to the latest fashions to international news and even weather reports. Of the author himself, the Cambridge History reports that he “had a keen curiosity about things and people past and present, a retentive memory and a gift for gossip.”

The goal of the book seems to be one of eclectic variety organized around the years of the author’s life. As Smith puts it in his preface:

Some may object to my vanity, in expecting the reader of the following pages to be pleased with so heterogeneous a dish. It is, I own, what ought to be called salmagundi; or, it may be likened to various suits of clothes, made up of remnants of all colours. One promise I can make, that as my pieces are mostly of new cloth, they will last the longer. Dr. Johnson has said: “All knowledge is of itself of some value. There is nothing so minute or inconsiderable, that I would not rather know, than not.”

The book is bound in wonderfully sturdy feather-marbled boards with deep brown leather spine and corners. There are six compartments with raised bands down the spine with decorative tooling and a black leather title band with gold lettering. The edges of the pages, the inside of the front and back covers, and the recto of the front flyleaf and verso of the back flyleaf all share the same colorful marbling pattern.

The pages measure 12cm x 19.5cm and are quite healthy, with very little foxing and no tears or damage (except for the front fly, which is coming loose at the top). There are no watermarks or chain-lines; the paper was, as with almost all non-specialized printing paper after 1805 in England, wove-made on a machine. The book’s pagination runs [i]-iv, [1]-311 (the first edition may be distinguished from the second in its pagination; it runs up to 306). Its collational formula seems to be 8o: [#] [A2] B12-O11: $1, 2, 3 [5]. Thus, it seems to be an “octavo in twelves” (a full sheet folded in eight with a half-sheet folded in four).

On the verso of the front fly, and inserted after the fly (on a slip of stationery from Botleys Park Hospital Management Committee of Chertsey in Surrey) are an assortment of owners’ marks. Those written on the fly are cryptic and are combination of various pencils and a purple stamped “N6L”; the pencil marks include the notation "Finneron, Woking. Nov | 54".

Pasted on the slip of stationery, in the same hand as the “Finneron, Woking. Nov | 54” notation (though annotated in black and blue inks, not pencil) are slips of paper cut from advertisements for various editions of the book. The slip advertising the 1905 edition is annotated with “Myer, London. Jan | 57”; the first slip advertising the 1845 edition (first) is not annotated; the second slip advertising the 1845 first edition is annotated “Beaucham<> London. 1960”; the final slip advertises Mackay’s 1846 adaptation and is annotated “Hammond, B’haus. Oct | 56”. Whomever bough the book was apparently fastidious about recording its values in various editions when they came up for sale; if the inscription on the fly is the mark of when and where it was first purchased by this owner, it seems that he or she bought the book from E. J. Finneron, a bookseller in the English town of Woking since at least 1935.

There are two bookplates, and these bring me back to the topic of tracking down interesting provenances and the larger conceptual idea of the interconnectedness of our books through their past proximity to one another.

One bookplate shows a hunter’s horn, tied and apparently hanging from a bowed ribbon, on top of a barrel that is lying on its side. The cryptic initials JFTD encircle the horn in a clockwise direction. The second bookplate, pasted on the inside of the front cover, is more clear: a ribbon reading “Sub Tegmine Fagi” (“Concealed Beneath the Beech Tree”) crowns a beech tree that rises from a particolored band. Below this crest is the owner’s name: Henry B. H. Beaufoy, F.R.S. (“F.R.S.” stands for Fellow of the The Royal Society).

Beaufoy (shown below) was likely the book’s first owner. From roughly 1784 through 1843, Beaufoy was one of Europe’s most celebrated and prestigious hot air ballonists; his numerous ascents contributed unprecedented support to the nascent discipline of aeronautics, as well as providing new information to cartographers, meteorologists, and physicists in England and on the continent. Beaufoy was also a great collector of both coins (he wrote a well-regarded book on early English “tokens”) and, more importantly for my purposes, books. Beaufoy collected across a range of topics and genres. Most famously, however, was his assembling together in one library a copy of the first (1623), second (1632), third (1663), and fourth (1685) folios of the plays of William Shakespeare (his library was dispersed at auction by Christie’s in July 1909 and the four folios were eventually split up at auction in July 1912). To put it briefly, then -- and to return to this post’s initial premise -- holding Beaufoy’s copy of A Book for a Rainy Day is likely to be as close as I’ll ever come to all four of the seventeenth century Shakespeare folio collections at once.