The intersection of the visual arts with poetry has a rich and complicated history. Truly effective poems are (in my view) a form of visual art as much as verbal art: by evoking concrete and moving sensory images, these poems can create just as specific a visual scene as any painting or photograph. Indeed, by appealing to the unique imagination of each reader, in some ways such poems succeed in creating an even more specific visual scene as any form of visual art could do. Nonetheless, it is not uncommon to see artwork juxtaposed with poetry in collections of verse -- the practice has been around since the very first poems were scribbled down on papyrus, parchment, and vellum.

This week’s book is an example of a poetry book that later had photographs added to it in order to “enrich” the contents.

The title is Sun and Saddle Leather, a collection of twenty-two “cowboy poems” by the famed, first poet laureate of early twentieth-century South Dakota, Charles Badger Clark, Jr. (1883-1957). A legendary outdoorsman, traveler, and speaker, Clark’s poems, articles, pamphlets, novels, and stories gained him fame as the “voice” of the last generation of rugged pioneers of “the Old West”. He lived, wrote, and entertained visitors in a cabin that he himself built, with no running water, heating system, or electricity, surrounded only by the woods of Custer State Park in the Black Hills and by his herd of pet deer.

Clark’s book was first printed by Richard Badger’s Gorham Press of Boston (I can find no evidence that the publisher was related to Charles Badger Clark) in 1915. It was widely-read (though only one copy of this first edition is currently on the market) and eventually a copy reached L. A. Huffman (1854-1931) all the way out in Miles City, Montana.

Huffman had already begun to gain fame for his Western photographs: starting as a post photographer for General Miles’s army at Fort Keogh, by 1916 he had taken six thousand pictures of the people, wildlife, and landscape of the lands surrounding Yellowstone, mostly using “crude cameras” (as Ruth Hill, Richard Badger’s editorial assistant put it) of his own making. To supplement his work as a photographer, Huffman operated a small book, photo, and print-selling business out of his studio.

Huffman was ecstatic about Clark’s poetry and contacted the Gorham Press to order two hundred copies for his own retail sale in Miles City. Badger promptly sent them and then invited Huffman to contribute photographs to the forthcoming second edition (of which Huffman would eventually order five hundred copies to sell). My copy is of this second edition, which Badger published in 1917 and which was simultaneously published in Canada by The Copp Clark Company of Toronto (Badger published another edition in 1919 and again in 1922, followed by later editions from Boston’s Chapman & Grims in 1936 and the Westerners Foundation of Stockton, California in 1962). The title page of the second edition includes Badger's device: a classical figure hauling on a printing press beneath a trellis, over a banner with the words "Arti et Veritati".

The second edition is a slender volume, bound in black paper-covered boards, with a title label in red text on the front board and another on the spine. It run to 60 pages, with the illustrative plates inserted unpaginated and not integral to the gatherings in which they appear.

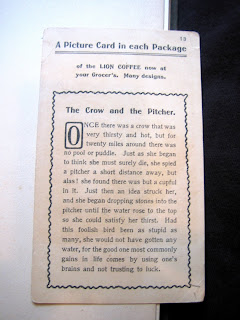

The only evidence of readership in my copy is a piece of ephemera stuck in between the first blank flyleaf and the cover. It’s card #13 of a collectible series of “picture cards” issued by Lion Coffee in the 1960s (manufacturers of products often used such “collect the whole set” ephemera, such as cards, in order to induce people to keep buying their product -- a tactic that McDonald’s Happy Meals and similar products still use). This card features a watercolor on one side and the story of “The Crow and the Pitcher” on the other (the resourceful crow, thirsting for some water, drops stones into the pitcher to raise the water level to the point where she can drink it).

In total, Huffman contributed eight grayscale photographic plates to the new edition (including the frontispiece), each keyed to a specific line or image in one of Clark’s poems. They are almost all wide, sweeping panoramas of the western plains, peppered with the small figures of cattle, men on horseback, and the occasional dog, tree, or similar slight perturbation of the otherwise flat horizon. A few capture action shots of the cowboys in mid-lasso or mid-trot.

Clark’s poems paint concrete pictures of the western landscape and the people and wildlife that populated it in the earliest years of the twentieth century. Though occasionally conventional in its imagery and uninventive in its prosody (heavy doses of the ABABCDCD stanza rhyme scheme), the book strikes a tone that gives one the sense of actually hearing a cowboy speak about what he has seen and experienced on the trail: the language is frequently idiomatic, the references very particular, the spellings often recreate the twang, accent, and peculiar dialect of the Old West.

In many ways, then, Clark’s poems serve as well as any audio recording would in capturing the aural quality of life on the wide and rolling plains of the Dakotas. Having never been out there myself, I don't know how much of this kind of lifestyle and language still survives, but Clark's poems certainly capture a time from the past that may be well on its way to becoming unrecoverable -- if it isn't completely gone already. Combined with Huffman’s early photos of the visual life of the region in the period, the poems of the second edition of Sun and Saddle Leather transport the reader to an entirely different time and place -- which, after all, should be one of the goals of any good book.

No comments:

Post a Comment