There are certain printers and publishers whose works must

be part of any book collection that strives to assemble the most

representative, important, and beautiful examples of the book as an historical

artifact and an aesthetic object. Most of those works are, alas, far beyond the

means of the modest book-collector (to say nothing of the grad student book

collector). But every once in a while, a real gem falls into the patient

collector’s hands.

There are certain printers and publishers whose works must

be part of any book collection that strives to assemble the most

representative, important, and beautiful examples of the book as an historical

artifact and an aesthetic object. Most of those works are, alas, far beyond the

means of the modest book-collector (to say nothing of the grad student book

collector). But every once in a while, a real gem falls into the patient

collector’s hands.

This week’s book is a tiny volume that I obtained at New

England Book Auctions earlier this month. The title is Catullus Tibullus Propertius Cum C. Galli Fragmentis quae extant –

a collection of verses by the Roman elegiac poets Gaius Valerius Catullus, Albius

Tibullus, and Sextus Aurelius Propertius, along with fragments by Gaius

Cornelius Gallus. The book was published by Lowijs (that is, Louis) Elzevir (as

was conventional, he used a Latinized forename in the imprint: Ludovici) in

Amsterdam in 1651.

This mini-anthology of influential Roman poets was a

standard publication for early Lowland stationers, appearing first in Antwerp

in 1569 followed by a very successful edition at Amsterdam by William Jansson Blaeu in 1619 and

again in 1626, 1630, 1640. Elzevir’s edition may have comprised at least

two different printings, though, lacking access to other copies, I’m not

entirely certain to which my copy belongs.

To relate the history of the Dutch Elzevir (actually

“Elzevier” but it has become Anglicized to “Elzevir”) family in full would

require much more space and time than I can give here; for the interested

reader, some excellent resources are available in print, including David

Davies’s The World of the Elseviers,

1580-1712 (The Hague, 1954) and Edmund Goldsmid & Alphonse Willems’s

very useful Complete Catalogue of All the Publications

at the Elzevier Presses (1885; for my book, see i:80). The patriarch of

the family, the original Louis Elzevir (the grandfather of the man who printed

and published my book), was trained at various printing and bookselling firms

around the Netherlands, most notably serving a turn with the master printer and

innovator of the “Plantin” press, Christophe Plantin. By 1580, Elzevir was in

Leiden, where he started the shop that would become a major family enterprise

up until 1712 (though it underwent some geographical moves to various urban

centers around the Netherlands and Belgium, including, by the time my book was

printed, to Amsterdam).

In total, the family issued over 1,600 titles, including the

last piece of writing by Galileo at a time when the astronomer’s works were

forbidden in print by the Catholic Church. Without doubt, however, the most

famous Elzevirs (the generic term used for their books) were the exquisite,

artful tiny editions – mainly of classical authors – printed in the first three

decades of the seventeenth century. These small publications are considered

highly collectible, though the mania for them has fallen off since the

nineteenth and eighteenth centuries. Elzevirs are notable for their decorative bindings, their clarity of type and ornamentation, the quality of

their paper, and the neatness of their structure. So well-made were they that

most have stood the test of time with confidence. My copy comes from the period

just after this golden age, but it still demonstrates (in a later style) all of the same factors

that made the Elzevirs of the 1620s and 1630s so popular. Goldsmid gives the

following brief account of my book’s printer, Louis Elzevir III (1604-1670), of

the third generation of the family:

In total, the family issued over 1,600 titles, including the

last piece of writing by Galileo at a time when the astronomer’s works were

forbidden in print by the Catholic Church. Without doubt, however, the most

famous Elzevirs (the generic term used for their books) were the exquisite,

artful tiny editions – mainly of classical authors – printed in the first three

decades of the seventeenth century. These small publications are considered

highly collectible, though the mania for them has fallen off since the

nineteenth and eighteenth centuries. Elzevirs are notable for their decorative bindings, their clarity of type and ornamentation, the quality of

their paper, and the neatness of their structure. So well-made were they that

most have stood the test of time with confidence. My copy comes from the period

just after this golden age, but it still demonstrates (in a later style) all of the same factors

that made the Elzevirs of the 1620s and 1630s so popular. Goldsmid gives the

following brief account of my book’s printer, Louis Elzevir III (1604-1670), of

the third generation of the family:In 1637, this son of Justus Elzevier, of Utrecht, established a bookselling business in Amsterdam, and in 1640 added to it a printing press; but many of his books for many years were printed by the Leyden House. Relations were also opened with the house of Hackius, of Leyden; and many books published by Louis issued from their presses; and so good was the work, so clear the type, that many books printed by Hackius might be compared with the best work of the Elzeviers themselves. Louis Elzevier was a man of vast knowledge, the intimate friend of Holstenius, Vossius, and Descartes. His affairs prospered, and the house of Amsterdam soon equalled in importance that of Leyden. Between 1640 and 1655, it produced 219 publications: a large number for one man to superintend. As we have seen, in this year he was joined by his cousin Daniel, and from that day the Amsterdam press produced the Latin Classics, 12mo, of which the Leyden House had had a monopoly. At the age of sixty, in 1664, Louis Elzevier withdrew from business. After that date, we only find his name on one book, the folio French bible of Desmarets, which appeared in 1669. It had been begun many years previously, and was one of the most splendid works produced by the Elzeviers. Thus Louis closed his career with a masterpiece. He died the following year, from a compound fracture of the leg. He left to his nephew Daniel most of his share in the house, and Daniel purchased the remainder from the executors. [xvii-iii]

In total, over his career, Louis III was apparently

responsible for at least 381 titles in the span of 26 years, or approximately

15 editions per year.

One of those, of course, was the family’s only edition of

Catullus. The book is a compact 6.5cm x 11.5cm; the paper is a well made laid

stock with very faint horizontal chain-lines at 2.5 cm apart and no evident

watermark. The edges of the pages are red all around. A blue silk marker is

built into the binding. The binding itself is, being an Elzevir, a fantastic

example of craftsmanship and – I confess – the reason I obtained the book: full

calf boards over which on front and back is pasted a glossy paper that has been

given a heavy surface sizing and then marbled in dark and light brown (the

decorative sheet means that the only leather actually visible is along the

spine and on the corner tips of the boards). The spine comprises five compartments separated

by raised bands with gilding; in the second compartment is a gilded title

(“Catullus”). Even more fantastic than the marbled paper on the boards are the

endpapers: the front and rear fly-leaves and pastedowns are a heavy paper

(again, given a good sizing, though not as deep as the paper on the boards)

that has been slightly marbled with a rich blue background over which appears

an elaborate white pattern of knotted lines, vines, and flowers. The papers

were clearly cut out of a larger sheet that may have been used in Elzevir’s

shop for endpapers in other books as well (to ascertain whether the binding was done in the shop or was done on commission by the owner -- as was common in the period -- it would be fruitful to compare this

to other Elzevirs from 1650-1652).

One of those, of course, was the family’s only edition of

Catullus. The book is a compact 6.5cm x 11.5cm; the paper is a well made laid

stock with very faint horizontal chain-lines at 2.5 cm apart and no evident

watermark. The edges of the pages are red all around. A blue silk marker is

built into the binding. The binding itself is, being an Elzevir, a fantastic

example of craftsmanship and – I confess – the reason I obtained the book: full

calf boards over which on front and back is pasted a glossy paper that has been

given a heavy surface sizing and then marbled in dark and light brown (the

decorative sheet means that the only leather actually visible is along the

spine and on the corner tips of the boards). The spine comprises five compartments separated

by raised bands with gilding; in the second compartment is a gilded title

(“Catullus”). Even more fantastic than the marbled paper on the boards are the

endpapers: the front and rear fly-leaves and pastedowns are a heavy paper

(again, given a good sizing, though not as deep as the paper on the boards)

that has been slightly marbled with a rich blue background over which appears

an elaborate white pattern of knotted lines, vines, and flowers. The papers

were clearly cut out of a larger sheet that may have been used in Elzevir’s

shop for endpapers in other books as well (to ascertain whether the binding was done in the shop or was done on commission by the owner -- as was common in the period -- it would be fruitful to compare this

to other Elzevirs from 1650-1652).

I understand from some of my regular readers that they were

saddened I did not provide a collation formula for the Beaumont and

Fletcher folio several

weeks ago. In an effort to redress this fault, I offer the following

formula for this week’s book: 24o in 8s: [π2] A8-B8

(±B1)

C8-P8 (±P8) Q8-R2 [#2]: $5 (- E4, F3, I1).

The precise placement of the two cancellandum indicated in the formula [see photo, right], as well as the cancellans that replace

them, is speculative; short of taking apart the binding to inspect conjugate

pairs (which, of course, I won’t do, since I bought this book expressly for its

binding) I cannot say for certain if B1 above should in fact be A8 and if P8

should be Q1.

The pagination runs for 131 leaves, [1-2] 3-70 [71-72] 73-128

[129-130] 131-260 [261-2]. The unpaginated internal leaves (71/2 and 129/30)

are the section title-pages for Tibullus and Propertius. I found one intriguing

error in the placement of a pagination number on D7v: the “62” is in the inner

corner (that is, to the right of the running title) instead of the proper outer

corner for a verso page; this suggests a momentary lapse of concentration on the

part of the compositor. Otherwise, however, there are no errors in pagination

or in catchwords either within or across gatherings. The page heads in the running titles

throughout change depending upon the section of the book; slight variations

across sheets within those sections indicates that a skeleton forme was not

used.

The pagination runs for 131 leaves, [1-2] 3-70 [71-72] 73-128

[129-130] 131-260 [261-2]. The unpaginated internal leaves (71/2 and 129/30)

are the section title-pages for Tibullus and Propertius. I found one intriguing

error in the placement of a pagination number on D7v: the “62” is in the inner

corner (that is, to the right of the running title) instead of the proper outer

corner for a verso page; this suggests a momentary lapse of concentration on the

part of the compositor. Otherwise, however, there are no errors in pagination

or in catchwords either within or across gatherings. The page heads in the running titles

throughout change depending upon the section of the book; slight variations

across sheets within those sections indicates that a skeleton forme was not

used.

The position of decorative devices and borders throughout

the volume can help recreate the way in which the printing team executed their

work. On A2r there appears an upper border and a decorative majuscule “C”. On

E2r, after the “finis”, there is triangular vine device with what looks like

(but isn’t) a set of numerals on top (80208). On E3v, the “finis” is

followed by a device of a horned face surrounded by scrollwork above, flies to

each side, and a crab below. The same upper border ornament and a decorative

majuscule “A” of the same style as the “C” on A2r appears on E5r and – with an

“S” this time – on I2r; the same horned head that appears on E3v is used on

E5v. The numeral ornament appears again on H7v. An entirely new triangular

ornament of a face surrounded by vines and flowers is used on I3v and again on

R2v. The duplication of the horned head on E3v and E5v is the only place where

one ornament, peculiarly, appears twice on a single sheet.

But perhaps the most peculiar fact about the disposition of devices

and ornaments in the book is that with the exception of the one at the

end of the book on R2v, they are absent from gatherings K through Q. This

absence cannot be explained as a function of space-saving, as many of the

places in which devices appear in the early gatherings (at the head of new

chapters or as tail-pieces in the blank spaces beneath “finis”) continue into the later gatherings;

similarly, the places where a decorative majuscule is used in the early

gatherings are constrained to using simple majuscules in the late gatherings. I

suspect that another practical explanation is most likely: Elzevir had another

work in a different press at the same moment and the compositors in the shop

were sharing a device case; the worker putting together the type for the

other job monopolized the devices at the point when the worker on the Catullus was in gathering K of his

(there is no clear evidence in the typography of the book to suggest that a second

compositor took over in the latter half of the book, though this too is a possibility).

But perhaps the most peculiar fact about the disposition of devices

and ornaments in the book is that with the exception of the one at the

end of the book on R2v, they are absent from gatherings K through Q. This

absence cannot be explained as a function of space-saving, as many of the

places in which devices appear in the early gatherings (at the head of new

chapters or as tail-pieces in the blank spaces beneath “finis”) continue into the later gatherings;

similarly, the places where a decorative majuscule is used in the early

gatherings are constrained to using simple majuscules in the late gatherings. I

suspect that another practical explanation is most likely: Elzevir had another

work in a different press at the same moment and the compositors in the shop

were sharing a device case; the worker putting together the type for the

other job monopolized the devices at the point when the worker on the Catullus was in gathering K of his

(there is no clear evidence in the typography of the book to suggest that a second

compositor took over in the latter half of the book, though this too is a possibility).

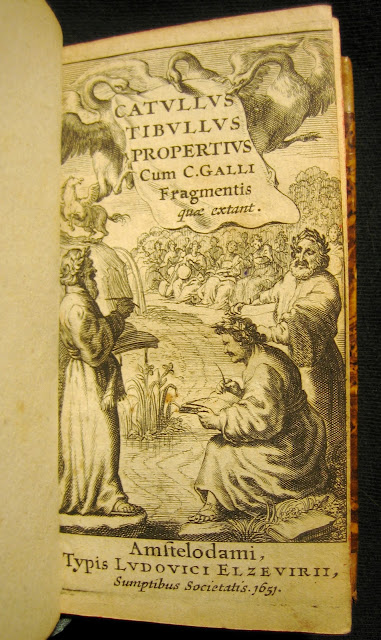

The contents, not including fly-leaves, are as follows:

blank (not integral); title page with unattributed illustration of three poets

at work and the nine muses watching, Pegasus on a cliff, and three geese

overhead holding the book’s title (blank verso) (1-2); Pietro Crinito’s life of

Catullus (3-6); selection of Catullus’s poems (7-67); the “Perviglium Veneris”

with the note “quod quidam Catullo tribuunt” ["that some attribute to Catullus"]

though the poem is probably by Tiberianus (68-70); the life of Tibulla from

book three of Crinito’s book on Latin poets (73-6); Tibullus’s Equitis Romani (77-125); Ovid’s elegy on

the “immaturam mortem” ["premature death"] of Tibullus (127-8); the life of

Propertius, again from book three of Crinito (131-34); poems by Propertius

(135-235); a brief life of Gallus from an unspecified source (236); poems by

Gallus (237-54); three Gallus epigrams with notes by Aldus Manutius (255-9); a

fragment from “dialogue four” of Giglio Giraldi’s history of poetry (260).

The book has seen some use. At least two readers have marked

it up in slight ways. One reader used faint red underlining on many pages and

other marginal notations (for example, a “4” beside a poem title on p. 151

[K4r] and an “x” beside titles on p. 190 [M7v], p. 202 [N5v], p. 228 [P2v]). In

some places an attempt was made to erase the red underlining, which has

subsequently weakened the paper and lightened the print – an example of how

sometimes dealers’ and collectors’ urge for

“clean” books can actually result in physical damage to the book itself (there

are horror stories of attempts to bleach margins in old books

defacing the book itself, to say nothing of wiping out any potentially valuable evidence of the

book’s provenance or use). Another reader has added a few marks in gray pencil,

including underlining two lines on p. 119 (H4r) and inserting (sometimes crudely formed) checkmarks in places (for example, p.

239 [P8r] and p. 244 [Q2v]). As with most marginalia, given time one could

recuperate from the marked passages a sense of what these earlier readers’

interests and objectives might have been in reading (and possibly acquiring)

this book. Another cryptic owner’s mark appears on the recto of the blank

before the title-page. This mark, which may be an owner’s name, is written in

an elaborate eighteenth-century hand with ornate flourishes, but it has become

so worn that it is now nearly impossible to read.

A final owner’s “mark” accompanies the book, though it is

not part of the volume itself. To protect the fine Elzevir binding, a

thoughtful previous owner has fashioned a custom-made variation on a drop-spine

box made of fine and sturdy red boards on the outside and containing a

rectangular opening within a raised inner bed decorated with a marbled red

paper that echoes slightly the marbled paper on the binding of the book itself.

No doubt Louis Elzevir himself would be proud to see the product of his

craftsmanship still very much intact and nestled safely in such a well-made but also elegant setting.

No comments:

Post a Comment