To celebrate my grandfather’s eightieth birthday, this week’s book is one he recently gave to me for my birthday and which centers around a character whose adventures my grandfather tells me he used to read when he was a boy.

The book is actually two volumes in one. The first is Peck’s Bad Boy and His Pa and Compendium of Fun, Profusely Illustrated, a collection of stories written by George Wilbur Peck (1840-1916) and published by Stanton and Van Vliet, Co. of Chicago, in 1911. The title page proclaims that this is the “Complete Edition” and is accompanied by 100 illustrations by True W. Williams (1839-1897), who gained his own fame as illustrator for stories by Samuel Clemens (Mark Twain). The book was first published in 1883 under the title Mirth for the Million: Peck’s Compendium of Fun, Comprising the Immortal Deeds of Peck’s Bad Boy and His Pa, and All the Choice Gems of Wit, Humor, Sarcasm, and Pathos. In the same year, the first edition was followed by a stand-alone narrative, The Grocery Man and Peck’s Bad Boy. The stories themselves had almost all first appeared, however, in Peck’s weekly newspaper, The Sun, beginning in 1874. The Bad Boy quickly gained famed far beyond Wisconsin, however, and a Canadian edition followed in 1884, a Swedish edition in 1898, and additional U.S. editions in 1893, 1895 1900, 1905, 1907, and 1911, along with a scattering of other Bad Boy adventures published separately (including the collection of songs “Peck’s bad boy songster” in 1884 and, in 1907, Peck's bad boy with the cowboys: relating the amusing experiences and laughable incidents of this strenuous American boy and his pa while among the cowboys and Indians in the Far West).

In 1885 the character was so well known and loved that Atkinson’s Comedy Company, at the Boston Theatre, on Washington Street in Boston, presented “scenes in the every day life of Peck’s bad boy and his pa, without plot, but with a purpose, to make people laugh, the only authorized dramatic version, in three acts, of the celebrated Bad boy sketches, by Geo. W. Peck”, adapted for the stage by Charles F. Pidgin. Even after Peck’s death, other American writers continued the Bad Boy’s adventures, such as James Austin’s Return of Peck’s Bad Boy between 1920 and 1952. Several modern publishers have also released contemporary reprint editions, ensuring that the Bad Boy can continue to entertain readers. Besides the Bad Boy’s appearance on stage, he was also to be seen on the silver screen three times (1921, 1934, and 1938) and was, along with Austin’s unauthorized sequel, the inspiration for a short-lived comedy television series in 1959, Peck’s Bad Girl, which ran for only 14 episodes.

In his own day, Peck made quite a name for himself beyond his humorous stories. Born in New York, he moved to Wisconsin at a very young age and stayed there the rest of his life. He took to the newspaper life and founded his own papers in Ripon and later La Crosse. In 1878, the La Crosse paper -- The Sun -- moved with Peck to Milwaukee and became Peck’s Sun. Peck’s love of his new hometown led him to run for mayor on the Democratic ticket and win -- despite the fact the majority of voters in Milwaukee were Republican. His electoral success in the metropolis was then translated by the Party into a successful bid for governor in 1890, a position he held until 1894.

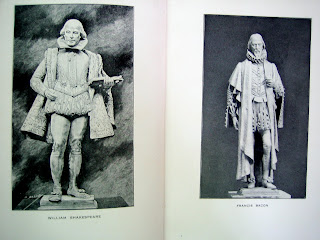

The book is hardback bound in red cloth, with an illustration of the titular character smoking a cigarette and chatting with an older man; a closer look at the Bad Boy’s grinning face appears on the spine. The pages are, with the exception of the photographic plate of the author, unfortunately printed on an old acid-based paper. The stock of this paper was quite flimsy to begin with and it has since faded over time -- though the illustrations and text are still clear. Beside this fading and some chipping to some pages, though, the book is in good shape. It was printed in small octavo format, but there are no signatures to mark the gatherings so I’ll spare us all the trouble of jotting down a collational formula for this one.

As noted above, the book actually consists of two parts. The first is Peck’s Bad Boy and His Pa, which is itself divided into two volumes (36 chapters in the first; 27 in the second). The second part of the books is Peck’s Sunshine: A Collection of Articles Generally Calculated to Throw Sunshine Instead of Clouds on the Faces of Those Who Read Them, consisting of 59 chapters and a number of additional illustrations as well. These stories are not about the Bad Boy but are in the same vein of anecdotal humor, all of the tales -- some true, some fictional -- first appeared at various times in Peck’s newspapers. The illustrations for this volume were done by “Hopkins” (whomever that might be). Peck’s Sunshine was originally published by Belford, Clarke, & Co. in 1882, followed by later editions in 1892, 1893, and 1900 by other publishers and has also been more recently reprinted by modern publishers as well.

The preliminaries of the first volume are paginated [i]-[xvii], with a blank flyleaf and the photographic plate inserted between the first [i-ii] and second [iii-iv] leaves of the gathering. The first volume’s contents are paginated 23-347 and I’m not sure why the numbering starts so oddly. The pagination in the second volume is equally inexplicable; the preliminaries run [i]-iv, followed by an author’s note (“Not Guilty”) numbered 23 in the lower inside corner and then the contents of the volume, which run 1, 8-124. The final page is a blank fly made of heavier stock. One intriguing feature of the table of contents in the second part and the lists of illustrations in both parts is that they are provided in alphabetical order, rather than in sequence. This likely points to the episodic nature of the book: it was intended for readers (many of whom may have already been familiar with many of the stories and may have deliberately sought out certain titles) to pick through the stories intermittently and selectively, rather than to read straight through the chapters consecutively.

The only indications of previous readership are an owner’s name illegibly inscribed on the recto of the front fly (“D. Je< >l<>”) and a folded piece of old lined paper used to mark a reader’s place between pages 60 and 61 of the second volume (the story that starts on page 61 being “Woman-Dozing a Democrat”).

At the head of both volumes are author’s notes that put the book into its proper context and thus deserve quoting in full. The first, “A Card from the Author”, states:

Gents—If you have made up your minds that the world will cease to move unless these "Bad Boy" articles are given to the public in book form, why go ahead, and peace to your ashes. The "Bad Boy" is not a "myth," though there may be some stretches of imagination in the articles. The counterpart of this boy is located in every city, village and country hamlet throughout the land. He is wide awake, full of vinegar and is ready to crawl under- the canvas of a circus or repeat a hundred verses of the New Testament in Sunday School He knows where every melon patch in the neighborhood is located, and at what hours the dog is chained up. He will tie an oyster can to a dog's tail to give the dog exercise, or will fight at the drop of the hat to protect the smaller boy or a school girl. He gets in his work everywhere there is a fair prospect of fun, and his heart is easily touched by an appeal in the right way, though his coat-tail is oftener touched with a boot than his heart is by kindness. But he shuffles through life until the time comes for him to make a mark in the world, and then he buckles on the harness and goes to the front, and becomes successful, and then those who said he would bring up in State Prison, remember that he always was a mighty smart lad, and they never tire of telling of some of his deviltry when he was a boy, though they thought he was pretty tough at the time. This book is respectfully dedicated to boys, to the men who have been boys themselves, to the girls who like the boys, and to the mothers, bless them, who like both the boys and the girls.

Very respectfully,

GEO. W. PECK.

Peck's Sunshine begins with the following address:

Gentlemen of the Jury:

I stand before you charged with an attempt to "remove" the people of America by the publication of a new book, and I enter a plea of "Not Guilty." While admitting that the case looks strong against me, there are extenuating circumstances, which, if you will weigh them carefully, will go far towards acquitting me of this dreadful charge. The facts are that I am not responsible. I was sane enough up to the day that I decided to publish this book and have been since; but on that particular day I was taken possession of by an unseen power—a Chicago publisher—who filled my alleged mind with the belief that the country demanded the sacrifice, and that there would be money in it. If the thing is a failure, I want it understood that I was instigated by the Chicago man; but if it is a success, then, of course, it was an inspiration of my own.

The book contains nothing but good nature, pleasantly told yarns, jokes on my friends ; and, through it all, there is not intended to be a line or a word can cause pain or sorrow—nothing but happiness.

Laughter is the best medicine known to the world for the cure of many diseases that mankind is subject to, and it has been prescribed with success by some of our best practitioners. It opens up the pores, and restores the circulation of the blood and the despondent patient that smiles is in a fair way to recovery. While this book is not recommended as an infallible cure for consumption, if I can throw the patient into the blues by the pictures, I can knock the blues out by vaccinating with the reading matter.

To those who are inclined to look upon the bright side of life, this book is most respectfully dedicated by the author.

GEO. W. PECK.

The book is, of course, a product of its day and contains some language that modern readers would find offensive (racial epithets, for example) and some situational humor that modern readers would find distasteful (a running thread throughout the Bad Boy’s early adventures are his attempts -- sometimes malicious, sometimes guileless -- to catch his Pa in the old man’s attempts to engage in extramarital romantic escapades...attempts that often succeed spectacularly but that also almost always end with Pa giving the boy a sound beating out in the woodshed and the boy speculating on a life on the road, in the circus, in a hotel, etc.). Equally dated is Peck’s manner of telling the Bad Boy stories in what he took to be the dialect of young boys of the time and place (the stories are told in the first person from the Bad Boy’s point of view), an informing detail in revealing how an older man heard and interpreted the slang and speech-patterns of boys of his day.

The nature of some of the narratives can be suggested by reference to some of the more telling chapter titles and their under-headings, such as the title of this post. For example, chapter four of the first part of the book, “The Bad Boy’s Fourth of July”:

Pa is a Pointer, not a Setter -- Special Arrangements for the Fourth of July -- A Grand Supply of Fireworks -- The Explosion -- The Air Full of Pa and Dog and Rockets -- The New Hell -- A Scene that Beggar’s Description

Or chapter five, “The Bad Boy’s Ma Comes Home”:

No Deviltry, Only a Little Fun -- The Boy’s Chum -- A Lady’s Wardrobe in the Old Man’s Room -- Ma’s Unexpected Arrival -- Where is the Hussy? -- Damfino! -- The Bad Boy Wants to Travel with a Circus

Or chapter twenty-three of the second volume, in which the Bad Boy, his Pa, and the Grocer and Minister (both also targets of the Bad Boy’s shenanigans) get involved with amateur dramatics in “The Grocery Man and the Ghost”:

Ghosts Don’t Steal Wormy Figs -- A Grand Rehearsal -- The Minister Murders Hamlet -- The Watermelon Knife -- The Old Man Wanted to Rehearse the Drunken Scene in Rip Van Winkle -- No Hugging Allowed -- Hamlet Wouldn’t Have Two Ghosts -- “How Would You Like to be an Idiot?”

The chapter headings of the second part of the book are also revealing and include such gems as “A Bald-Headed Man Most Crazy”, “An Aesthetic Female Club Busted”, “Female Doctors Will Never Do”, “Fooling with the Bible”, “Shall There Be Hugging in the Parks”, and “The Naughty but Nice Church Choir”.

Overall, the stories glorify the eccentric and sometimes cruel nature of boyhood in late nineteenth-century and early-twentieth century middle America -- a tradition from which emerged not just Peck’s Bad Boy but those other iconic rapscallions who embodied our nation’s own larger transition from the whimsical fantasies and devious pranks of childhood to the dark humor and often frustrating inequalities one becomes aware of in the process of maturing to adulthood, the immortal Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn.