A couple of weeks ago I wrote about the worthwhile goal of

owning an example

imprint from specific, influential printers, such as the House of Elsevir.

This week’s book picks up that theme again, though in this case the book in

question is from the family of an important early publisher rather than

printer.

While Ben Franklin might be the more familiar name as a

major early American printer-publisher, the name of radical patriot and

newspaperman Isaiah

Thomas (1749-1831; shown above in a portrait owned by the American Antiquarian Society) is perhaps just as important though perhaps less well

known. Beside printing revolutionary newspapers – many of which were the first

of their kind in the colonies – Thomas also published books, perhaps most

importantly a series of children’s books by author John Newberry. In his time,

the Thomas empire produced more than 1,000 titles (far more than any of his

rivals, including Franklin) and was bolstered by many shrewd business moves,

including buying a book bindery in Worcester in 1782 and progressively opening

branches and partnerships in Boston, Newburyport, Springfield, Vermont, New Hampshire,

New York, and Baltimore. In addition to magazines, newspapers, almanacs, and

other ephemera, the books from Thomas’s sixteen presses included the first

American editions of major English novelists such as Laurence Sterne and Oliver

Goldsmith, the first American novel (The

Power of Sympathy, or, The Triumph of Nature, 1789, by William Hill Brown),

and the earliest American edition of Mother

Goose (1786). His decision to acquire the copyright to all of Noah

Webster’s spelling and grammar books, in 1789, proved a particularly shrewd

investment. After his development of the first truly successful interstate

publishing and retailing network in the history of America’s book trade,

Thomas, in his retirement after 1802, penned the monumental and still relevant History of Printing in America (in

which he provides the first comprehensive and authoritative description of the

people and firms at the heart of the country’s colonial and late 18th-century

through early 19th century book industry) and in 1812 founded the American Antiquarian Society in

Worcester, whose vast collection of pre-1876 American imprints (most donated by

Thomas) is rivaled only by the Library of Congress.

One of my goals has been to acquire a Thomas imprint – book,

pamphlet, or newspaper – in good condition. This week’s item comes close: like

the Elsevir I wrote of before, however, this item is from a later family member in the trade. Upon

his “retirement” from the trade in 1802, Thomas passed his business on to his

son, Isaiah Thomas, Junior (for simplicity, I will refer to Thomas, Junior as

Thomas from this point; if I refer to the father, I will use Thomas, Senior).

Like his father, Thomas rested a substantial portion of the firm’s income upon

that always reliable staple of the industry: textbooks.

This book is The Understanding

Reader: or, Knowledge Before Oratory, Being a New Selection of Lessons, Suited

to the Understanding and Capacities of Youth, and Designed for Their

Improvement. Its goal is to teach students about "Reading”, “The Definition

of Words”, and “Spelling, Particularly Compound and Derivative Words.”

The title-page promises that the book offers “A Method Wholly Different From

Any Thing of the Kind Ever Before Published.” It also offers an observation

attributed to Ben Franklin: “Our boys often read as parots [sic] speak, knowing

little or nothing of the meaning.” The book is by Daniel Adams

(1773-1864), a Leominster, Massachusetts-based academic and physician who eventually

moved to New Hampshire, where he became a state legislator in 1838. Adams’s

textbooks were popular and this was no exception, going through over two dozen

editions from various publishers between its first printing (by [Daniel] Adams

& Wilder for Adams, in 1804) and its last (by Hori Brown of Leicester, MA

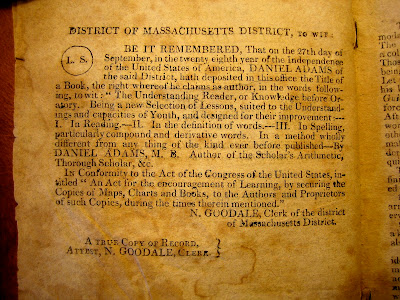

in 1821); according to the lavishly descriptive copyright statement on the

verso of the title-page (typical for its day), the book was entered for

copyright in Massachusetts by the Commonwealth’s district clerk (and Salem

native) Nathaniel Goodale, on “the 27th day of September, in the

twenty eighth year of the independence of the United States of America” (that

is, Sept. 27, 1804; because Adams’s preface is dated “Leominster, Sept. 29,

1803” some descriptions of the book by dealers, Wikipedia, etc. misattribute

the copyright to that date – instead, oddly, it seems that nearly a full year

elapsed between Adams’s completion of the book and its appearance in print).

This book is The Understanding

Reader: or, Knowledge Before Oratory, Being a New Selection of Lessons, Suited

to the Understanding and Capacities of Youth, and Designed for Their

Improvement. Its goal is to teach students about "Reading”, “The Definition

of Words”, and “Spelling, Particularly Compound and Derivative Words.”

The title-page promises that the book offers “A Method Wholly Different From

Any Thing of the Kind Ever Before Published.” It also offers an observation

attributed to Ben Franklin: “Our boys often read as parots [sic] speak, knowing

little or nothing of the meaning.” The book is by Daniel Adams

(1773-1864), a Leominster, Massachusetts-based academic and physician who eventually

moved to New Hampshire, where he became a state legislator in 1838. Adams’s

textbooks were popular and this was no exception, going through over two dozen

editions from various publishers between its first printing (by [Daniel] Adams

& Wilder for Adams, in 1804) and its last (by Hori Brown of Leicester, MA

in 1821); according to the lavishly descriptive copyright statement on the

verso of the title-page (typical for its day), the book was entered for

copyright in Massachusetts by the Commonwealth’s district clerk (and Salem

native) Nathaniel Goodale, on “the 27th day of September, in the

twenty eighth year of the independence of the United States of America” (that

is, Sept. 27, 1804; because Adams’s preface is dated “Leominster, Sept. 29,

1803” some descriptions of the book by dealers, Wikipedia, etc. misattribute

the copyright to that date – instead, oddly, it seems that nearly a full year

elapsed between Adams’s completion of the book and its appearance in print).

The Thomas firm evidently obtained the copyright shortly after – perhaps almost

concurrent with – the appearance of the first Adams & Wilder edition. This

particular title is an excellent demonstration of the reach of the Thomas

empire, for most of his editions were printed in different cities and towns

around the country and for retail by different specific booksellers in those

cities and towns, but nearly all of them were published by Thomas and bear his family’s name. Like his father

before him, Thomas mastered the lucrative art of book wholesaling.

My copy is of the sixth edition of The Understanding Reader. It was published by Thomas – who

prominently points out in his imprint that he is the “Proprietor of the Copy

Right” – and “Sold Wholesale and Retail by him in Worcester, and by all

the principal Booksellers in the

United States.” It was printed by Ebenezer

Merriam (1777-1858) in Brookfield (today’s West Brookfield), Massachusetts;

the relationship between the Merriam firm, which specialized in textbooks, and

the Thomas family was a productive one, even after the Merriams left Brookfield

for Springfield in 1831. Eventually, in 1843, the Merriams would obtain from

the Thomas clan the copyright to one of their most successful titles, Webster’s Unabridged Dictionary, giving

rise to the title by which the book is more generally known today: The Merriam-Webster Dictionary.

The final page, T6v, presents one of those intriguing

publisher’s advertisements that reveals a bit about the book market at the time

of publication. The advertisement, headed “Valuable School Books”, notifies

readers that “[t]he following valuable School Books are published by ISAIAH

THOMAS, Jun. and are kept constantly for Sale at his respective Bookstores in

Boston and Worcester, Wholesale and Retail; also by said THOMAS and WHIPPLE,

Newburyport.” The titles listed are Scott’s

Lessons on Elocution, Murray’s

Abridgment of English Grammar, the third Worcester edition of Murray’s English Grammar (copied from

the sixteenth London edition; the blurb gives evidence of the pride Thomas took

in his work: “No pains nor expense have been spared in rendering the Third

Edition worthy of the liberal patronage which the former Editions have

received; and the Proprietor thinks he may justly pronounce this Edition

superior to any impression of the work in America; and he flatters himself,

that by its increasing demand, he shall be remunerated for the expense and

labor he has bestowed”), Parish’s

Compendious System of Universal Geography, and Perry’s Only Sure Guide to the English Tongue (“the proprietor

thinks no other recommendation can be necessary than only to mention that from

THIRD to FORTY THOUSAND of the Improved Edition of Perry’s Spelling Book sell yearly”). The ad ends with a note that, “The

Trade are informed that they can be supplied with any of the above in Sheets or

Bound, in large or small quantities, on as low Terms as any similar works are

sold for in the United States.”

As with most such textbooks, the aim of Adams’s book is to

expand and enrich the student’s command over vocabulary and spelling in

anticipation of his or her later lessons in rhetoric and oratory. The contents

comprise sample passages, organized by themes, in some instances being extracts

drawn from notable sources (from Milton to Franklin and the Bible to

Goldsmith); in the margin beside each passage, Adams has pulled out in italics

the key vocabulary word for the student to master. In an innovative use of

pointing, those words that the student is to learn to spell are marked with a

period and those that the student is to learn to define are marked with “a note

of interrogation” (i.e., a question mark). Glancing through the book, it’s

difficult to resist the temptation simply to read down the margin and imagine

the words there are some kind of surreal staccato dialogue out of a lost play

by Samuel Beckett.

As with most such textbooks, the aim of Adams’s book is to

expand and enrich the student’s command over vocabulary and spelling in

anticipation of his or her later lessons in rhetoric and oratory. The contents

comprise sample passages, organized by themes, in some instances being extracts

drawn from notable sources (from Milton to Franklin and the Bible to

Goldsmith); in the margin beside each passage, Adams has pulled out in italics

the key vocabulary word for the student to master. In an innovative use of

pointing, those words that the student is to learn to spell are marked with a

period and those that the student is to learn to define are marked with “a note

of interrogation” (i.e., a question mark). Glancing through the book, it’s

difficult to resist the temptation simply to read down the margin and imagine

the words there are some kind of surreal staccato dialogue out of a lost play

by Samuel Beckett.

Adams’s preface bears quoting at length in several places

because of the insight it affords into early American pedagogical theories about

how, and why, students learned to read and use language. First, after

explaining the punctuation system and how teachers can use it to drill students

who have practiced with the book, Adams explains the “advantages to be derived

from accustoming youth to give definitions of words”; the value of this, he

insists, goes beyond “simply that of becoming acquainted with the meaning of

them”:

1. Their minds will be excited to inquiry. In this way they will arrive to an understanding of many ideas of the Writer, which otherwise would have been wholly lost to them.

2. It will enlarge their acquaintance with language, not only by a knowledge of those particular words which they would define, but also by bringing many new words to their view.

3. It will help them to a readiness and facility of expressing their ideas. There is nothing in which frequent use and practice do more for a man, than in this one thing. If a man has never been accustomed to express himself on any subject or thing, he will be much put to it and appear exceeding awkward at first, however well he may understand the subject on which he would speak.

4. It will inspire them with a confidence in themselves, and in their own understandings, which will go further and be of more use to them on any public or private occasion than whole months or even years declamation on the stage.

The ideas Adams presents hint at dual nature of early

American teaching: it was both rooted in the classical and often mechanical

systems of the European Renaissance (memorization, oration, etc.) and also

pushing towards the more open-ended and progressive systems of the American

Enlightenment and soon-to-develop education reform movement (provocations to

inquiry and exploration, the inspiring of confidence, training in the tools in

addition to the content of learning, etc.).

At the same time, however, Adams – like most compilers of

textbooks for children in the period – understood that the kinds of material he

set before students, the ideas

presented in the extracts, would also be of paramount importance in shaping

their young minds and instilling in them “proper” thoughts and conduct.

Finally, at the end of each chapter, Adams provides a set of questions about

the content of the section and encourages teachers to pose such questions to students

in order to ensure that on top of mastering the language they are also grasping

the ideas presented to them (which span natural history, geography, literature,

biblical narrative, and morality).

The paper is a typical early-19th century cheap

wove stock often seen in textbooks of the period; they measure 11cm x 17cm. The

binding is an unremarkable, thick tanned pigskin – a hide that, given its

extreme durability, was a frequent choice for binders of early textbooks – cut

very unevenly and glued inexpertly onto the boards (probably done by an amateur

or owner rather than Thomas’s bindery; as indicated by the ad quoted above,

Thomas, like other publishers, often sold his textbooks unbound and the buyer

would be responsible for binding or paying for binding). There’s no printing on

the binding, but it does look like a faint handwriting is on the back board; it

is now, however, illegible. The book is 228 pages and may be described

collationally as 2o in 6s: [#] A6-T6 [π]: $1 and 3 [as miniscule

with “2”]. There are no catchwords and no errors in either pagination or

running titles, which are identical throughout the book (except for the

preliminaries, which were printed on sheet A) and suggest the use of a skeleton

forme. There are a few obvious compositional errors – such as setting “thier”

instead of “their” – and, judging from frequent blotting, the inking was

evidently done quickly and with little regard for precision. In general, the

book is in fair condition with some chipping on the binding and some tears to

pages and water stains throughout the block with no loss of text and no loose

pages.

Aside from a pen squiggle on p. 185 (Q3r) there are no

marginal markings. A previous owner has inserted three slips of paper, but

these seem to be meant simply to mark the book’s only three (unattributed)

illustrative plates (a reindeer on p.39; a camel on p. 124; and an elephant on

p. 177). There is, however, some owner’s provenance on the front flyleaf. On

the recto of the leaf a cursive, early ninteenth-century hand has written

“Caroline P. Goodnow’s” and, beneath that in a lighter ink, “Caroline P.

Goodnows | Book Febry 24th 1816”. The only precise match

that I can find for this name in any historical records is a Caroline P. Goodnow

who married Captain Lucius Brigham in Princeton, Massachusetts, in October

1832. One genealogy website guesses that her death date was around 1848, but in

the New England Historic-Genealogical Society’s 1860 Genealogies of the Families and Descendants of the Early Settlers of

Watertown, Massachusetts she is described as still alive in October 1852

when her grandmother died at her house in Lexington at the impressive age of

104. Given the marriage date, it seems probable that this is the same person that

owned my book; as a young girl in the early 1810s, Goodnow purchased Adams’s Understanding Reader, possibly for

school purposes. It’s always exciting to

obtain a book bearing woman’s ownership provenance from an age when literacy

education for women was still struggling to gain a foothold. The fact

that Caroline Goodnow owned Adams’s book stands as a reminder that Adams’s own

casual assumption that his reader would be “a man” (see his goal #3, quoted above)

was, by the early 1800s, an already outdated social convention.

Aside from a pen squiggle on p. 185 (Q3r) there are no

marginal markings. A previous owner has inserted three slips of paper, but

these seem to be meant simply to mark the book’s only three (unattributed)

illustrative plates (a reindeer on p.39; a camel on p. 124; and an elephant on

p. 177). There is, however, some owner’s provenance on the front flyleaf. On

the recto of the leaf a cursive, early ninteenth-century hand has written

“Caroline P. Goodnow’s” and, beneath that in a lighter ink, “Caroline P.

Goodnows | Book Febry 24th 1816”. The only precise match

that I can find for this name in any historical records is a Caroline P. Goodnow

who married Captain Lucius Brigham in Princeton, Massachusetts, in October

1832. One genealogy website guesses that her death date was around 1848, but in

the New England Historic-Genealogical Society’s 1860 Genealogies of the Families and Descendants of the Early Settlers of

Watertown, Massachusetts she is described as still alive in October 1852

when her grandmother died at her house in Lexington at the impressive age of

104. Given the marriage date, it seems probable that this is the same person that

owned my book; as a young girl in the early 1810s, Goodnow purchased Adams’s Understanding Reader, possibly for

school purposes. It’s always exciting to

obtain a book bearing woman’s ownership provenance from an age when literacy

education for women was still struggling to gain a foothold. The fact

that Caroline Goodnow owned Adams’s book stands as a reminder that Adams’s own

casual assumption that his reader would be “a man” (see his goal #3, quoted above)

was, by the early 1800s, an already outdated social convention.

No comments:

Post a Comment